The devices we have at our disposal for keeping a game going tend to become more and more legalistic as the concept of fairness evolves into a prerequisite for playing a game well. They are there to assure that the game is fair.

We establish such devices because we discover that, as we become familiar enough with a game to get totally involved in it, we tend to become a bit untrustworthy.

You know, you get involved in the heat of the game, you want to take the game as seriously and as fully as you can, and, if given the chance, you might in the blind passion of playing find yourself more willing that you normally would be to do something that closely approximates cheating—especially if no one happens to notice.

It’s not that you’re trying to be bad or inhumane or anything like that, it’s just that you’re so deep into the game that everything you do or think tends to become a strategy.

In other words, when you really get involved in a game, you forget yourself. In fact, the fun of the game lies in the fact that you can forget yourself. But what might happen is that you forget yourself too much (Koven 30).

Imagine that you have an axe which over time starts to break down. First, the handle breaks and you replace it, continuing to use it for a while afterwards. Eventually, the head breaks too and you’re forced to switch it out for a new one. No piece of the original axe remains–is it still the same axe?

This paradox, is perhaps better known as The Ship of Theseus paradox, with a variety of different fiction and non-fiction counterparts. Essentially, this paradox questions what happens when you replace all parts of an object (or person, robot, etc.)–does it still retain its original “thisness” or haecceity? It’s precisely the problem we see when looking at the more recent legacy of Bethesda titles: namely Skyrim and Fallout 4. There have been no shortage of mods available for Bethesda games, even as early as Oblivion. In the pre-Skyrim craze era, mods were already available to do just about anything. Recently, on my news feed I saw that Bethesda has basically stated that they’ll continue porting Skyrim “as long as people keep buying it.” My first thoughts after reading that was, which version of Skyrim is that?

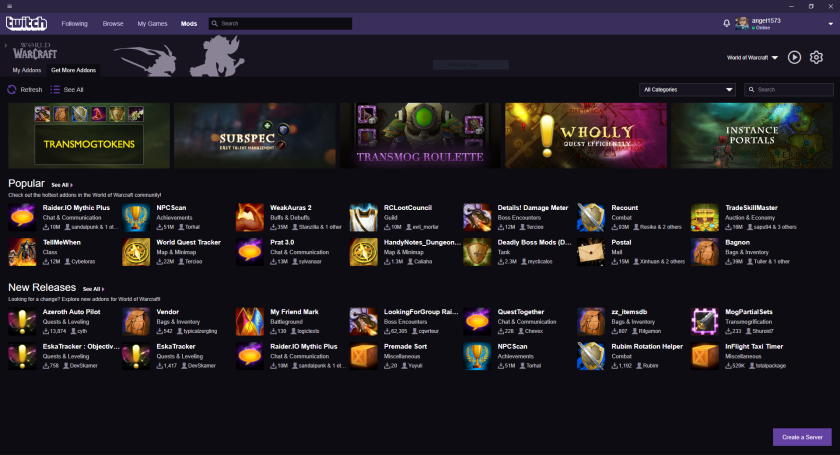

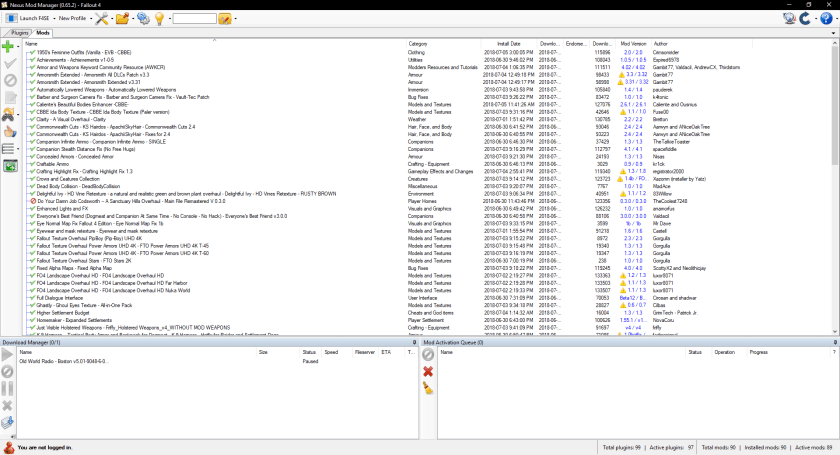

Although Bethesda clearly has a good sense of humour about it, the fact remains that one of the biggest parts of what has given Skyrim and many of its other titles such longevity, was thanks to its modding community. A quick search through most-popular-mod-source Nexus Mods reveals the depth and depravity of said community. Hosting mods for a wide-variety of games, including Skyrim and the Fallout series, options are sortable based on community downloads, approvals, and general popularity. The version of Skyrim/Fallout that the ‘community’ wants you to play, is often vastly different than the one originally produced by Bethesda. Mods like these come when you know the game too well, you’re in too deep, and just want to keep that world alive (Koven 30).

In addition to audio-visual overhauls, character model and NPC model updates, and minor UI tweaks, these kinds of mods also offer monumental bug fixes left hanging by Bethesda (I’m looking at you Xbox 360 Skyrim), quest design, loading screens, new user-designed quests, backstories, tutorial skips–you name it, someone probably has designed a mod for it. It’s interesting to note, that while I’m saying ‘mod’ to describe what’s available on Nexus, in truth, some of them can also be classified as cheats, and generally speaking, we’re back to the problematic division of cheats and modification, especially in the mods cycling around for Bethesda titles. How much of the game can we tweak or change before we’ve gone too far and created something altogether different?

Recently my boyfriend encouraged me to return to Fallout 4 after my last dismissal of the title, following a very disgruntled encounter with its Settlement building system. I couldn’t build what I wanted, where or how I wanted, and it all required far more investment into the game than where I was at at the time. The UI was clunky, and I just wanted to build my post-apocalyptic city in peace as a home base before continuing. After facing a critical-fail bug after an hour or two of work, I walked away from the game and never returned. My renewed interest came from the inclusion of mods, following the insistence that it would improve a lot of the issues I had, and it ended up being true. I fell into the Ibister flow and lost track of time within the game, but not for the reason of the game itself, I fell into it, because of the modding experience.

I had dabbled in Skyrim modding when I eventually made my transition from Xbox 360 to PC, predominantly due to mindnumbing bugs at every turn. Most of these mods centred on adding new customization for my character, as well as some audio-visual improvements, and UI tweaks–the usual stuff. One of these important features included adding a “real time” clock to my loading screens, as far too many hours were lost in the “just one more quest” world of Skyrim in my undergrad before that. With Fallout 4, things were different.

I spent an excruciatingly long time trying to get some of these mods to work in game, to work with one another, and to not generally break my ability to play the game. I made the foolish decision to start modding my game part way through an active save. While this was my first time getting this far, I didn’t feel comfortable incorporating mods or cheats that would break my “first” experience beyond the walls of Sanctuary. I would experience the “real” Fallout 4–or so I believed. It quickly became apparent that no matter what I did, I was changing the game beyond what it was “supposed to be.” A character interaction mod here, adapting how I chose my voice lines for chat interfaces, a “place anywhere” mod there, permitting my incessant need to build the perfect Settlements. My modding experience was about perfecting my experience within the Fallout space, all while trying to avoid doing as much damage to the game-as-intended as possible. It wasn’t about making it easier or harder, it was simply about improving the experience as it was–as determined by the community–like I was already so used to doing in WoW.

But I was wrong.

I made the mistake of remembering the existence of the console-command system. Alongside all the texture re-writes, the graphic overhauls, performance tweaks, and hundreds of hairstyles I had installed, I had yet to really “cheat” in my eyes, until I came to the console. Until this point, my boyfriend and I had been on the same page about what we were doing in the modvolution. Instead, I found as I got deeper into the game, that my opinions about cheating changed. I cared about the world, about my settlements, and about learning the story, but I cared less about how I went about building them or progressing through my murder sprees. I started implementing cheats for quick resources, alongside use of “killall” and “unlock” commands to get what I wanted without wasting too much time. I tried to use it sparingly, but it started to make the game feel emptier. If it weren’t for my desire to see the story or to make sprawling vaults and settlements, I don’t know if my heart would be in it. The ability to truly grind, to truly fail, to truly work for what I had given myself was missing (Juul).

With Skyrim, I had already beaten the majority of the game by the time I had started to dive into mods, and only ever did I cheat to advance my storyline the one time for my corrupted Xbox 360 save. The rabbit hole of cheating had encapsulated me, and now I was faced with trying to get clean or just commit to the deeds that I have done. Ironically, though his Fallout has the limit of mods, without cheating, my boyfriend’s Fallout may yet be more authentic than mine. A sentiment he shares, and that I might just believe.

It’s no wonder that Bethesda turns off achievements for players with modifications enabled (although with the Fallout 4 Script Editor, you can re-enable them anyway). With any number of mods enabled, even Bethesda seems to believe that having them changes the game enough that achievements are no longer valid when obtained on a modded system.

In looking back at my decisions to change Fallout 4, the how and the why, the community’s answers, and the community’s options–I can’t help but echo the idea of what “thisness” remains in the game after so many changes? Mods label themselves as vanilla or lore-friendly, suggesting that they’re closer to the game’s “thisness” than their counterparts. If the axe’s head you replace comes from the sister of the axe you already owned, does that make it closer to the same axe?

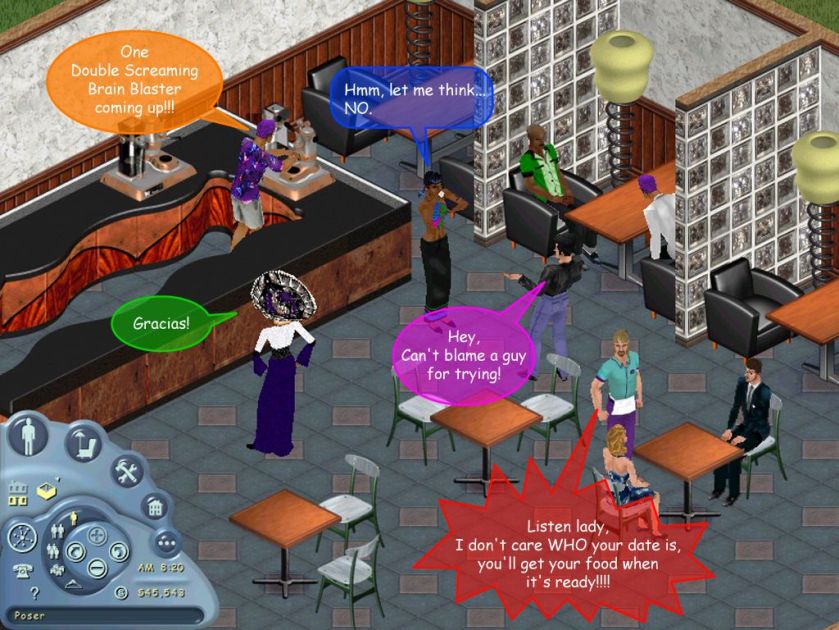

People cheat and modify these games for any number of reasons, primarily in finding new ways to establish their ideal user experience through improving identity (character, environment mods), flow (UI, ease or difficulty changes, performance enhancers), and even modifying what it means to fail. Through these changes, they reinforce community standards, while still toying around with what the developers have allowed them to change. While Fallout 4 and Skyrim allow for much larger changes to their core code than say, The Sims 4, World of Warcraft, or Sonic 2, any changes beyond simple interaction with the game-as-design call into question the “thisness” of a game.

We may cheat, modify, and break games for any number of inherent human desires to do so, however, is a game only what it’s produced to be, or should we begin to consider all changes, modifications, cheats, and adaptations to be part of the ephemeral haecceity that surrounds the initial game’s code? If we can adopt house rules as a relatively standard deviation from normal rules, and if Luxury Tax gets paid out to Free Parking on the regular, maybe modding and cheating aren’t so bad. Maybe they find ways to help us make use of our game worlds just a little bit longer. Or maybe, it’s simply a way for a gaming community to participate in the development world, beyond passive engagement.

After all, Skyrim played on Xbox 360, will differ from Xbox One, from the Switch, and from P.C., before mods or cheats are even considered. Why set the limits on user experience? As Koven stated in the quotation at the beginning of this series: “I am aware that the motivation for your sudden intensity stems not as much from your concern that I have broken a rule as from your feeling that I have somehow deprived you of your opportunity to win…” (24). If cheating is just a socially agreed upon set of rules and conditions of play, then what does it matter if no one is there to see you do it?

Academic References/Further Reading:

Isbister, Katherine How Games Move Us (2016)

Juul, Jesper. The Art of Failure (2013)

Koven, Bernard De. The Well-Played Game (2013)