Perhaps the most obvious way that players are drawn into video games is the development of their virtual worlds. Implicit/explicit storylines, graphic design, music, narration, voice acting, game mechanics, character development, and so much more. The components that go into building our gaming worlds are as complex and diverse as the genre conventions that seek to govern them.

We need an understanding that can assess the materiality of play as much as that of the ideas or the objects themselves. A game can produce meaning or, perhaps better stated, experience. But what kinds of experiential meaning can games generate, exactly?…Art and games are not anything unto themselves. The experience of an artifact is contingent on so many factors outside the control of the object itself, let alone the artist or designer: historical context, situational context, the prior experiences and knowledge of the individual, and so on. There is no set way for a game to unfold or for play acts to be performed. The space of possibility within a game is all potential, a potential realized through play (Sharp 105-106).

While traditional storytelling may be able to paint a world for our minds, giving us something to see (in some cases like Lord of the Rings, they do it exceedingly well), video games actually take us there. While Sharp goes on to make the argument that some games are more “artful” and complex than others, I would instead suggest that all video games are as complex as the players who play them. While the simplistic narrative and world of the early Super Mario Bros (1983) cannot compare to the depth of the more artistic and polished Braid (2008), it doesn’t mean that they don’t still have this “potential” for artful engagement. In the empty spaces of the world, of the narrative, left by developers, players will build in their own stories.

Not all games enthrall their players with fanciful explicit narratives or plotlines to follow. Instead some, like Overwatch, tell their stories in the background and in paratext (Genette and MacLean 1991). Through this subversive storytelling, Blizzard Entertainment has continually hinted at what would-be upcoming hero releases and inclusions into the existing game. The ever-evolving landscape of Overwatch facilitates this kind of artistic engagement. Players develop their own theories and their own narratives to bridge the gaps until Blizzard decides to fill them. Sometimes they even guess quite correctly. Alongside the maps and flavour text of this FPS online game, Blizzard also releases comics and video shorts to fill out the world and their story. They have even included two specialty seasonal game modes which allow players to play “Overwatch Missions” from the past. These actions by Blizzard help to ensorcell their playerbase in a realm of narrative intrigue. Fans also are heavily involved in creating art, fictions, or cosplay to further explore Blizzard’s world. In this way, they are enraptured by one another, and are building Overwatch together.

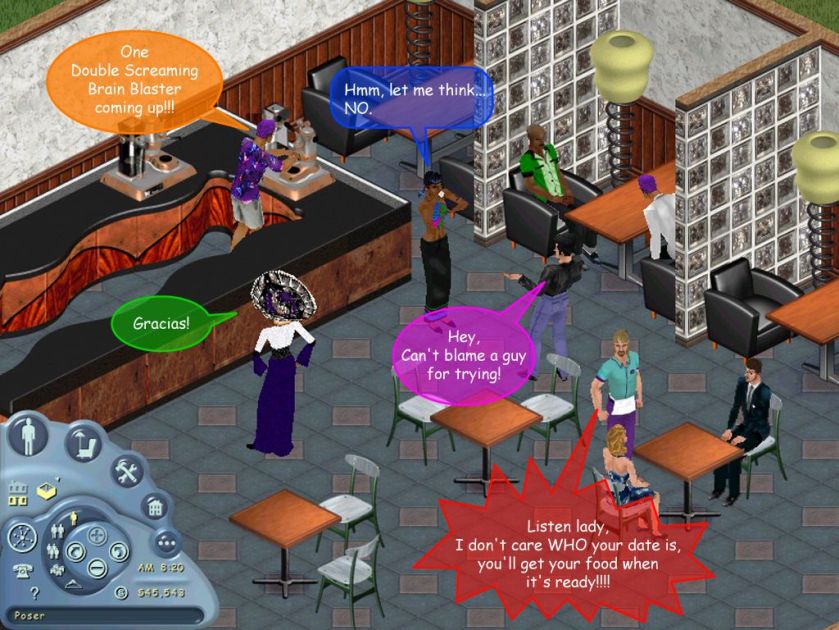

Alongside the divide between explicit or implicit storytelling, developers also continue to incorporate player decision and consequence into narratives for a new way of gaining their attentions. Consequence chains in games like Mass Effect, Fable, The Walking Dead, Skyrim, and Undertale shape not only the story being told, but also pose the player as an active agent within it. Even though decision trees are still very much part of a procedural progression (Bogost 2010), they give the illusion of control in the worlds they come to. The most successful of these is perhaps not explicit narratives like those mentioned above, but is instead better demonstrated by games like The Sims. I looked into this somewhat in my previous post on modding The Sims, however, in the context of player engagement, The Sims is the epitome of potential play at work. The Sims from the outset is practically a blank slate. The dollhouse ready to be played with.

While there are some story features to breathe life into the world, especially in later versions of the game (including decision trees for walks through the Wharf with your favourite pupper), the largest part of the storytelling in The Sims is done by the player. Even if the player does not actively consider the story, or the world they are building, they are still participating in its creation. Every Sim made, every house created, every simoleon spent–they are enacting the world in every stroke. Mod creators go so far as to extend the world, in a way that may parallel how fanfiction or fan art relates with more traditional narratives. These things get complex. In a game like The Sims, the only real limitations are those of your imagination. All the game platform really does, is to facilitate the world you want to create. Perhaps that’s why it’s developed such a following, and why creation-sim games are amongst the most common best-selling PC games of all time.

Giving players the option of choosing paths in gameplay narratives, engage not only their minds but also their emotions, further enhancing their immersion in the game’s world.

Curious about the outcome of ill treatment, Wright began to slap his creature—then was astonished to find himself feeling guilty about it, even though this was very obviously not a real being with real emotions. This capacity to evoke actual feelings of guilt from a fictional experience is unique to games. A reader or filmgoer may feel many emotions when presented with horrific fictional acts on the page or screen, but responsibility and guilt are generally not among them. At most, they may feel a sense of uneasy collusion. Conversely, a film viewer might feel joyful when the protagonist wins, but is not likely to feel a sense of personal responsibility and pride. Because they depend on active player choice, games have an additional palette of social emotions at their disposal (Isbister 8-9).

https://youtu.be/AA3jKpyn_AQ?t=30s

Alongside story development and narrative, graphics and musical scores comprise one of the key ingredients to video game immersion and engagement. Video game soundtracks and ambient sounds in particular seem an essential part of our gaming experience. Their intentional inclusion or exclusion can illicit a wide array of different responses in players.

The audio soundscape [of Waco Resurrection] enhances the player’s visceral immersion in the experience: at different points, the player hears FBI negotiators, battle sounds, even the voice of God. The artists included audio recordings that FBI agents played to disorient the actual compound members when they launched their assault (i.e., the sounds of drills, screaming animals, etc.) (Isbister 14).

I’m sad to say that, despite its importance in evoking emotional and visceral responses, this is one of the only mentions within How Games Move Us that discusses the importance of the soundscape in gameplay immersion. While graphical representations are important for connecting to our avatars and actually walking through a world, these are features that our minds can often fill in. It is the music and soundscape which truly draws players in, often without them realizing it.

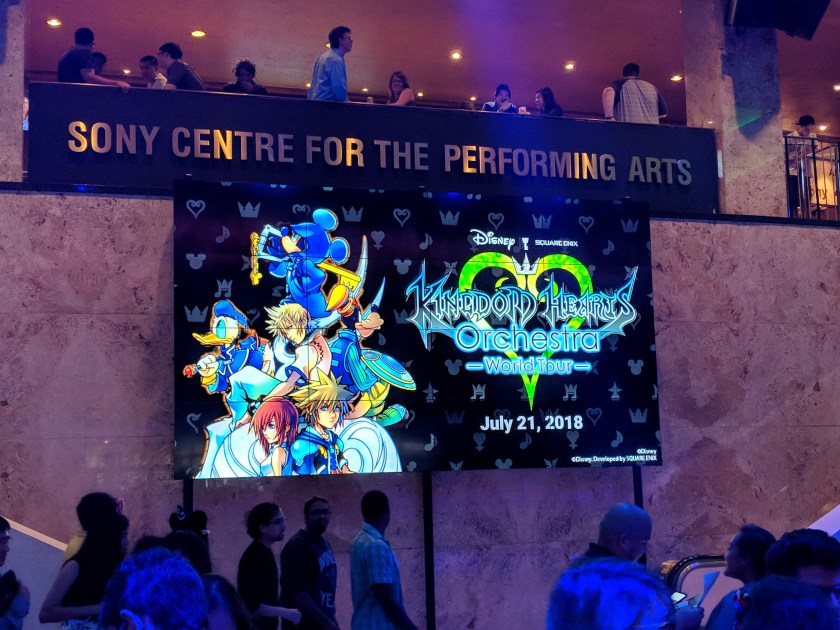

The immersive importance of game soundtracks and sounds is easily observable in the popularity of symphony tours like Video Games Live (above), Distant Worlds (Final Fantasy), or the Kingdom Hearts Orchestra World Tour. Video game music is designed to immerse us in what we’re doing, but not distract us from the task at hand. When relevant, it crescendos and brings us to our knees, never realizing the music that brought us to this breaking point.

For example, take the ending of Kingdom Hearts 1. While the theme song is found in various forms throughout the game, its placement at the ending is specifically to draw together all of the emotional buildup from the game and grab the audience one last time. Its lyrics are given greater meaning. It comes after a period of no music, following the dialogue of the protagonist and one of his best friends, as the worlds start to re-materialize around them, diving them on different shores. The song cuts in, just as their hands are ripped apart, the song continuing to play through the epilogue of the game’s emotional journey of friendship, light, and darkness.

I played this game at a very impressionable time in my life, at some point in high school. The game’s story and world had me wrapped in and obsessed for a long time, and arguably I still am, as I sit writing this in front of a full-scale replica keyblade (the game’s primary weapon). I lapped up all the information in the game as I could, side scraps of journal entries, secret cutscenes–as well as information outside of the game, Japanese special scenes, press releases, and most importantly, the soundtrack. I listen to the theme song from Kingdom Hearts 1 quite frequently, the same version that the game ends on. Listened to in this context, it provides nostalgic memories and warmth. However, after experiencing the emotional buildup of narrative, gameplay, and progression through the story, after reaching the crescendo of their hands being ripped apart, I cry every single time. The music alone is not to blame, but rather the journey and music paired which elicits such an emotional response.

Recently, I went to see the Kingdom Hearts Orchestra World Tour at the Sony Centre in Toronto. This scene played twice on the screen over the course of the concert. Once, near the beginning, it was part of a montage which included parts of this song. There was no emotional build up, no immersion to cause a response. However, they played the orchestral version of the theme song again in the epilogue/encore of the show. By this point, they had taken us through a large number of story beats through videos and synchronized symphonic song. They built us up to it. While the visual alone was not enough to send me into that emotional place, the build up of the music over time, was.

I left the theatre with weepy-eyes, having never touched a controller at all.

[Part 5]

– Genette, Gérard and Marie Maclean (1991) Introduction to the Paratext

– Isbister, Katherine (2016) How Games Move Us

– Sharp, John (2015) Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Art