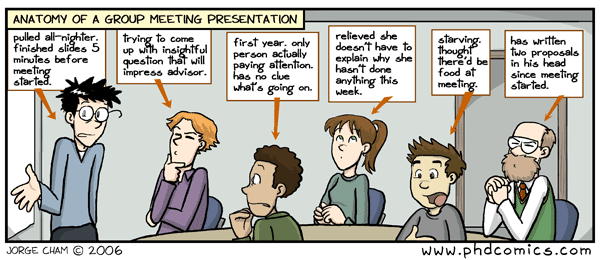

How I usually feel about group work:

However, this round has been rather spectacular. From the very beginning our group was quick to make decisions, to work together, and to adjust to each other’s strengths and weaknesses, including varying availability. Never did I feel like I was doing more work than my share, nor did I feel as though people weren’t available. But ultimately, it was quite a good experience. Most importantly, we learned from each other.

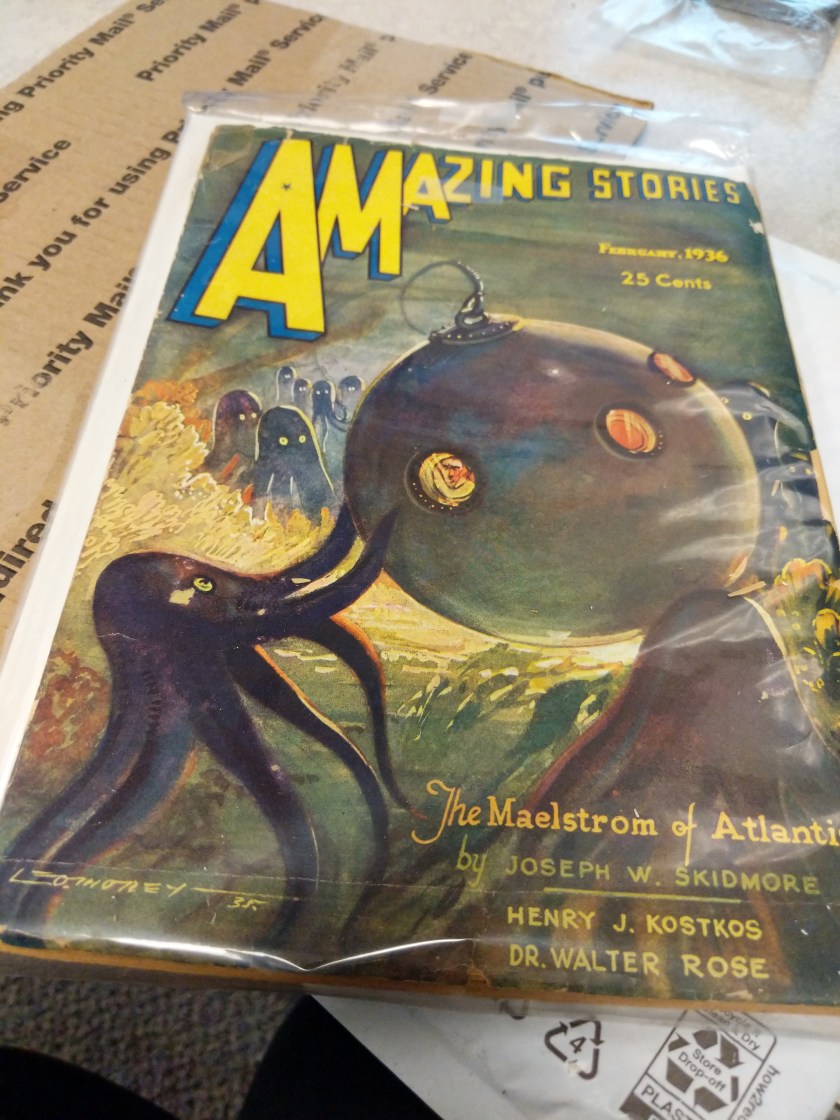

In preparing for our presentation, I was not only engaged with our magazine because of my own interests and foci, but also inspired by what my colleagues uncovered. I’m not sure if it helped that our magazine had a lot to go with it, or because I love Sci Fi so much, but it really helped me understand the magazine better too.

Equally, I found myself engaged with the other group’s presentations. It was clear to see where everyone’s passions lay, showcased by this project. Surprisingly, no one group or individual quite did the same thing, nor did anyone take the same angle on their pulp magazine, which was rather spectacular. It highlighted just how many ways that pulp magazines can be understood and interpreted from an academic perspective.

Best of all, the presentations left me inspired for my final paper for this course, which was an unexpected result.

Each group gave me a new reflection for my analysis of preservation practices in pulp magazines. Each one demonstrated the different ways in which approaching digitization holistically is crucially important.

While it’s a little early to go too in-depth (not to mention the idea is still forming), I was particularly inspired by the exploration of Snappy Stories and All Story Love Tales, for two very different reasons. All Story Love Tales because of how rare its digital issues are (or any issues at all for that matter), and Snappy Stories for its important and varying use of image accompaniment–and how those things change how one could read the magazine. Interesting stuff to be sure, and something I’ll be very eager to explore when I get down to writing more content for the paper.

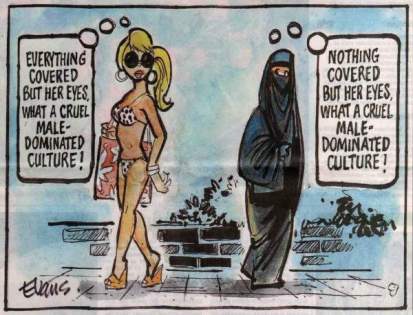

One of my favourite things to hear, no matter how frequently, in my academic courses is the importance of taking in multiple perspectives on a given topic–something that rings very true when considering analyzing artifacts. I think my first exposure academically in a formal capacity was when we discussed “situated knowledges,” something I touched on back here. It’s a concept that also comes up through Kenneth Burke’s “terministic screens.” We each see a different perspective on the world, on our studies. It is ever more apparent the need for academia to take this on in their approach to research — something which is exemplified by our group projects as well. Each group was given the same basic guidelines, and each of us came up with very different versions of what that meant to uncover.

For me, it seems that this is even more important for the study of pulp magazines within English departments. As an outsider to the discipline, it’s hard to see the magazines, so fruitful in their potential cultural relevance, interpretations, etc. be dismissed as trivial “low culture” objects. While we’ve discussed the changes taking place in this regard, coming from my own academic background, it doesn’t make sense that they have been dismissed as such. While it doesn’t always require deep reading to get to the messages within, it doesn’t mean that there isn’t any less content to discover. If anything, I think pulp magazines are more interesting to discuss, not only because there are so few academic angles currently being explored, but also because of how close they were to everyday people. It’s the same reason I find Greco-Roman graffiti so entertaining. Somewhat perplexing however, is the fact that greco-roman graffiti has been treated with such high significance as compared to their pop-cousins in pulp magazines. Perhaps this is due to their age, but everything starts getting old somewhere. Perhaps it was only after the classicists ran out of other things to talk about that they finally turned to the “common man” remnants. No matter what the cause, it is interesting to consider that someday down the line a great many people will turn to a desire to study pulp magazines, and it will only be because of classes like ours, and other enthusiasts, that archives like the PMP will provide them content. It pains me to consider how many pulp magazines were lost, like so many cultural artifacts, because they were deemed useless or “not cultural enough.”

If we, as individuals, and as groups, can uncover so much to talk about, what have we missed discussing over the past century they’ve been around?

Sadly, even fidget spinners someday will be a cultural artifact. I wonder what future academics will say about their phenomenon? I just wish I could hear what “ritualized” purpose fidget spinners served when uncovered by some archaeologist a thousand years from now. Food for thought I suppose.

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film