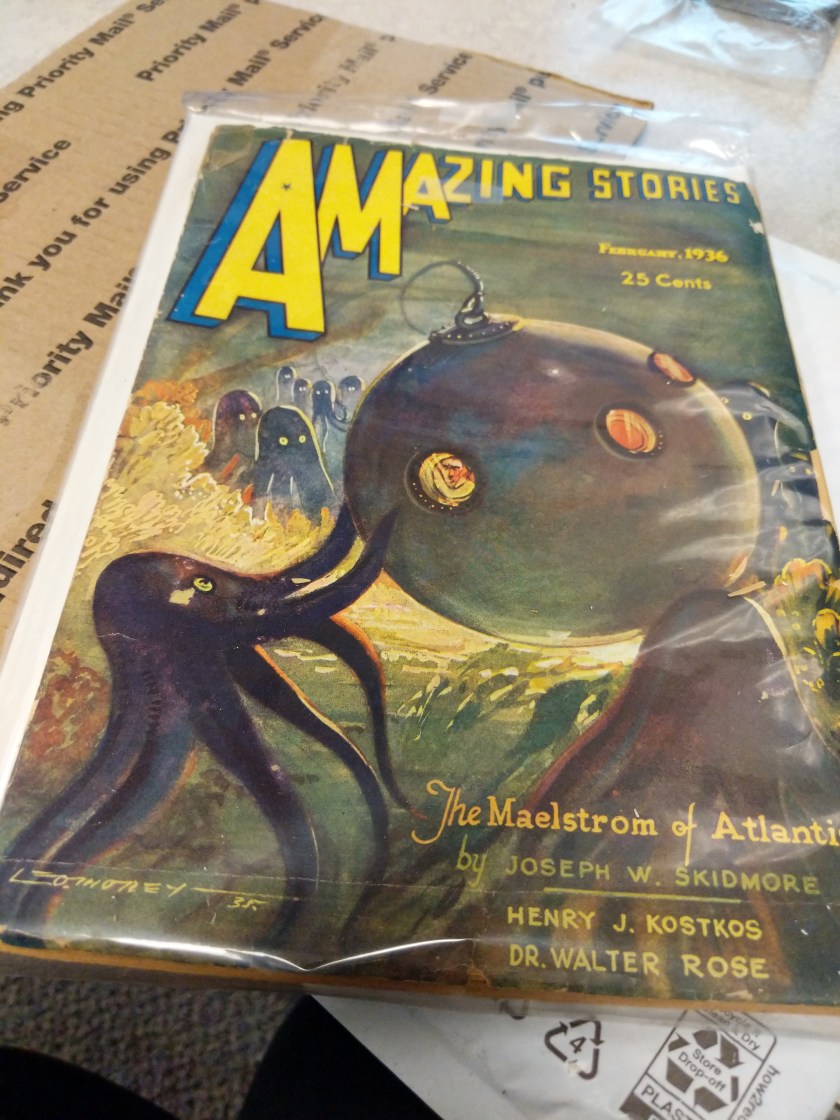

Before going too in-depth into my reflection on Sci-Fi and genre building, I just have to relay two facts: a) that there was a TV series in the mid-80s called Amazing Stories, created by Steven Spielberg, and b) that somehow I didn’t know this existed. In the same vein as the pulp magazine of the same name, the show apparently covered Fantasy, Horror, and Sci-Fi themes. It’s also apparently looking for a reboot. Crazy. Here I thought I was knowledgeable of these kinds of programs having watched The Twilight Zone (old and new) as well as The Outer Limits. Alas, I digress…

The creation of genre was not really something I had considered before this week’s class. Naturally I had considered that genres had origins — I have even studied the development of Greek and Roman theatre genres extensively — however, I have rarely considered that literary genres too, have origin stories. In particular, that there are more ‘recent’ genres like Sci-Fi that have a much longer legacy than what it feels like they should.

Perhaps it all comes down to definitions, however. We discussed this week how when Amazing Stories first published, the editor basically made it up as he went along. There were no established Sci-Fi pulps at this time, nor, apparently, had the genre been established as a literary area. Romances and Adventure stories are common throughout literary history, but Sci-Fi apparently presented something new. While I’d prefer not to quote Wikipedia, but the first few lines of “Science Fiction”‘s entry rings true, perhaps because they’re quoting Gernsback:

Science fiction is difficult to define, as it includes a wide range of subgenres and themes. Hugo Gernsback, who suggested the term “scientifiction” for his Amazing Stories magazine, wrote: “By ‘scientifiction’ I mean the Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision… Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading—they are always instructive. They supply knowledge… in a very palatable form… New adventures pictured for us in the scientifiction of today are not at all impossible of realization tomorrow… Many great science stories destined to be of historical interest are still to be written… Posterity will point to them as having blazed a new trail, not only in literature and fiction, but progress as well.”

To me it seems then, more that the development of SF as a genre was more about its kairos than its content. Alongside the development of advanced science and technology, we see something labeled accordingly. But even in the early days of writing (in terms of ancient plays), we see themes of instruction, knowledge transfer, and speculative/imaginative forms. While Gernsback cites Poe et al., we discussed in class the existence of Mary Shelley and other female authors before that also would fit into the SF genre (sadly calling again to those gender issues in scholarship and social acknowledgement). If these themes existed for longer than the existence of the genre, what else can we attribute the development of the genre to other than kairos? Someone surely could have “decided” to do so, as Gernsback did before Amazing Stories, and yet, no one did. Intentionality does not appear to be enough then, but rather, the timing not only of an increase in science and technology, but also the existence of pulp magazines themselves, that allowed for such a thing to develop.

Launching a new “genre” within literature would have been too risky. Books take a lot of time and finances in order to be successful, on top of necessary marketing and appeals to readership. Pulp magazines rose and fell seemingly at will — they were willing to take a chance, even if it meant failure — because they weren’t as expensive to produce. All of this explains why SF came when it did — easy to take a chance, lots of technology and science popping up everywhere…but it doesn’t account for all the reasons why they were successful…

I think the key here is the readership engagement. We’ll talk about this more during our presentation, or rather Sue will, but I think it’s worth spoiling a bit here on the subject. SF was successful as a genre due to its kairos as well as its ability to engage its audience. It’s quite a clever advertising move actually. The best way to establish yourself as a genre is to get people interested in your genre, to get them engaged in its development. People always love talking about themselves, and by extension, they love putting their mark on things. The actual amount of influence the readership had on Amazing Stories is up for debate, however, the magazine’s active push for any show of dialogue I think helped to make them boom as long as they did and really helped to engrain SF as a genre as a result.

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film Metropolis hit theatres as early as 1927. Then in 1938, Orson Wells converts his then-40 year old book The War of the Worlds into an infamous audio drama that briefly causes real panic and fear in the populace (The Smithsonian has a good piece on that and kairos/”an magnificent fluke” for the record). Meanwhile Astounding Stories kicks off in the 1930s as well. From this point forward, we see an increased basis for Futurism taking shape in art and design, especially leading through the 1950s and 1960s. Something we see revisited and taken to the extreme in the Fallout series.

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film Metropolis hit theatres as early as 1927. Then in 1938, Orson Wells converts his then-40 year old book The War of the Worlds into an infamous audio drama that briefly causes real panic and fear in the populace (The Smithsonian has a good piece on that and kairos/”an magnificent fluke” for the record). Meanwhile Astounding Stories kicks off in the 1930s as well. From this point forward, we see an increased basis for Futurism taking shape in art and design, especially leading through the 1950s and 1960s. Something we see revisited and taken to the extreme in the Fallout series.

In the end, I wonder what would have happened without this nexus of readership engagement and appropriate timing? Where would Sci Fi have started without pulp magazines? For how popular and how fast SF spread like wildfire in the last century, I feel fairly confident that simultaneous invention would have happened somehow, give or take a few years. But isn’t that all what SF is about anyway? Speculating the unknown?

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.