We’ve established every freedom we need in order to play well together. We know we can be silly when we want to, serious when we have to. We even know that we don’t have to do or be anything at all. But it’s different when you have to spend money for it. Even if you are only buying a game. It’s hard to take back. After all, that’s how games are sold. That’s how money is made. You buy it, and, baby, it’s yours forever (De Koven 105).

In more ways than one, money and time are huge factors in discussing how players engage with video games. There are obvious areas like barriers to games due to monetary reasons, or a lack of willingness to spend out of fear of lackluster content, but the reality runs much deeper.

The concept discussed in the De Koven quote above, is particularly interesting in light of the newest crackdown on ROMs and emulated content. I discussed this briefly in my post on the Game Genie and old cheat codes, but recently there’s been even more push against older content, with new laws valuing Nintendo ROMs at upwards of $150,000! The way things are going, Nintendo doesn’t even want you to be able to have ROM or emulated copies of the games you already own in physical formats. They want you to buy their updated version of the game, now that they have the NES and SNES Minis on the marketplace.

Many of us have nostalgic memories and value associated with our times spent with older games. In the digital age, and with old consoles no longer working, or no longer showing up properly on high-definition television screens, we sought other options.

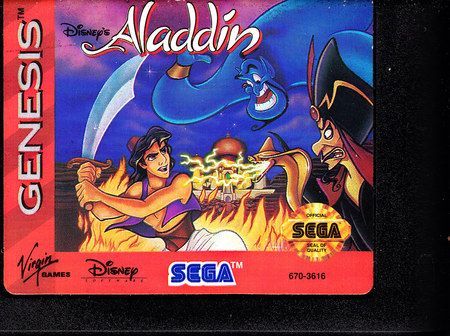

Over the years, I have physically purchased at least four different variations on a “Sonic Mega Collection,” via PS2, Xbox360, Nintendo DS, and most recently, via Steam. Sonic 2 for the Sega Genesis was the first video game that I personally owned the console. It’s forever held a very large place in my heart ever since. While I no longer own a copy of Sonic 2, I still have the original copy of Sonic 3 I received not to long afterwards. I spent countless hours spinning Sonic in all directions, clearing zones, gaining Chaos Emeralds. Through the time I invested, I was impressed upon. To this day, I still believe that Sega was ahead of its time and should have won the console wars. Alas, all I’ve been able to do, is to continue to support them by buying new versions of old titles. In truth, I don’t think any of my “collections” have received anywhere close to the attention they did when I was a child, and yet, I insisted on having a copy on whatever my gaming platform de jeur was. I also possess a number of ROMs and a Sega emulator for the titles I could less easily find: Aladdin, The Lion King, Jurassic Park (apparently I liked movie games).

In Nintendo’s new paradigm, the only way we can gain access to our nostalgia, short of owning the original copies, is to now hope that they deem the game you want worthy of being ported to the newest system. It doesn’t matter how much you invested in the past, they want to continue to take your money today, to resell you the experience you remember.

Not all monetary investment is quite so stark. Players can also become invested in their video games depending on the amount of money they have or have not spent.

By the time I transitioned to an N64 from my Sega Genesis, I continued to rent or borrow video games, and only had a very small collection of my own personal titles. Money was tight and while I had rented and beat The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, I had recently learned that the next instalment Majora’s Mask was set to release soon. I scrimped and saved leading up to the release date, and as luck would have it, I was able to buy the game pretty close to its launch. Naturally, my thirteen-year-old self had neglected to realize that Majora’s Mask required the memory expansion pack for the N64, which it did not come with, and which I did not possess. Saddened and disheartened, I quickly realized that I would be able to rent Donkey Kong 64 which came with the memory expansion, and be able to play Majora’s Mask without having to find money I did not have to buy one. In light of the struggle it took for me to acquire and finally play Majora’s Mask, it is a game I have a much stronger attachment to than the original Ocarina.

Looking back, many of my fond gaming memories and “favourite” games, have similar kinds of stories. My nostalgic attachment to my games came not necessarily just from the games themselves or my experiences with them, but the memories of how I received the games. My Sega Genesis made Sega king in my eyes for the early console wars. I favoured 007: The World is Not Enough over 007: Goldeneye, because it was the game I owned. These feelings were particularly strong in my youth, and now through the lens of nostalgia.

However, the reverse can now be seen as true. I have a modest but still overwhelming amount of games sitting in my Steam library. I have countless copies of dusty Xbox 360 and PS2 games sitting on my shelves, next to distantly-used consoles. I continue to buy games not only on Steam, but also for these seldom-used consoles. In the case of the consoles, because the titles somehow carry distant meaning from a long time ago, and sometimes even on Steam for the same reason–and yet I do not play them.

At what point can we officially call this out as being more about the joy of picking up cheap games than the games themselves? I’m not sure, but I suspect Valve zoomed past it in a rocket ship quite some time ago, and if we can still see it, it’s only because it’s doing a victory lap.

But of course, the sale is only part of the story. When it fades, what’s left? A long list of games with metaphorical bite marks that you tell yourself you’ll totally go back to, but which inevitably slide down the priorities list by dint of being so last month. Dim, blurred memories (Cobbett 2014 via Eurogamer).

What is to be said for this kind of lingering engagement or investment. If we continue to pay for the content, countless times over, and yet the titles simply sit on a shelf, or as clogged-up megabytes on a harddrive, how engaged can we possibly be? Is it instead engagement with a memory? Or are we more enthralled with the thrill of the good deal, as Cobbett suggests? Are we trying to bridge the gap in order to create meaning and connection to our pasts through whatever tangible means necessary?

Or perhaps, it’s some twisted version of the Sunk Cost Fallacy? One of the other kinds of investment and engagement we need to consider is the amount of time AND money that people put into their gaming experiences. DLCs, microtransactions, new equipment, fancy internet connections on the financial side, hours, days, months, or years on the side of time. “Your decisions are tainted by the emotional investments you accumulate, and the more you invest in something the harder it becomes to abandon it” (McRaney 2011). Basically, if you already feel you’ve already put a point-of-no-return amount into something (be it time or money), you’ll feel less inclined to leave it.

Common in the minds of gamblers, video game arcades are arguably one of the earliest attachments to this model. Have you been to an arcade recently? Do you remember what it’s like to drain quarter after quarter into a machine for another chance to get the next highest score? It sounds a lot like slot machines, and in some ways it was, just for score digits instead of monetary ones. Alas, modern micro-transactions, especially in mobile gaming, echo this model. In many cases, the game is designed to pull you along long enough, to make the rewards quick and ready enough, until things slow down. “I only have to wait a day for this thing to unlock” you may say to yourself. But you are impatient, and the ability to fast-track your research task only costs five coins, and you have fifty! Your one fast-track spirals into another, until you’ve quickly drained your coins. Suddenly you’re at the precipice of spending real money to gain more coins and progress further. You could wait, but you’ve already gotten this far, it’s only a little further.

Once money has been spent, especially on a game you’ve been playing long enough, it’s hard to turn back. Through this profit-model, ‘free’ games don’t stay free for very long.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy also applies to more complex games like MMOs. Once you’ve spent enough time or money into one MMO, it can be difficult to jump ship to a different one. There’s a fear of losing progress, of failing. “World of Warcraft is interesting in that it caters well to…three goal types: it can be played for the goal of reaching the current maximum level, but it is also possible to play with the improvement goal for acquiring ever more points, possessions, and higher social status, and it is common to play many characters to the maximum level, making it into a game of transient goals, to be reached multiple times” (Juul 87). If you’ve accumulated enough “wealth” of whatever goal you wish, it can be difficult to pull away and be the bottom of the totem pole. It can be easily argued that this is one of the ways in which World of Warcraft has remained so successful–it’s just so hard for people to leave altogether, especially if they’ve been playing a long time.

In order to get to that point, of course, a game has to be enticing enough of an environment to begin with. [Part 5]

– De Koven, Bernard. (2013) The Well-Played Game

– Juul, Jesper. (2013) The Art of Failure