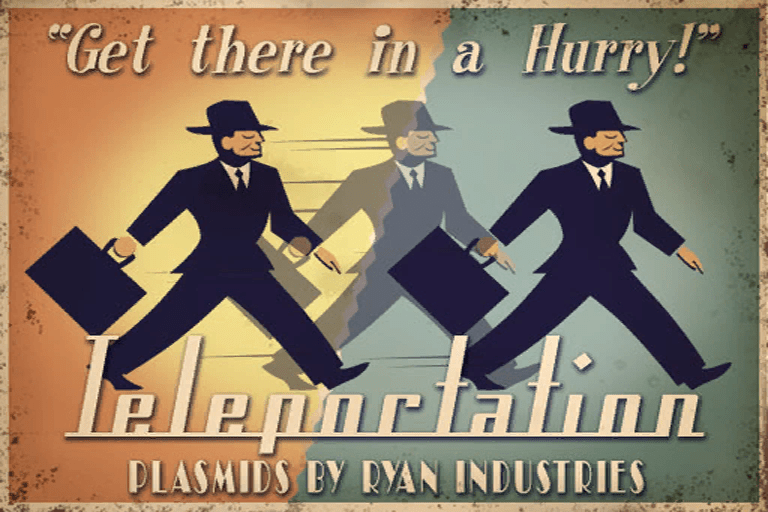

It’s hard to believe that we’re already at the end of term and tying things up. It feels like we’ve barely scratched the surface of this content, and maybe that’s kind of the point? As I talked about last week, there’s so much potential with pulp magazines to uncover. Maybe that’s why my head is spinning. There’s so much I want to talk about, so much to explore. I am still incredibly curious about the ties between videogame representations of the pulp era (mostly in exaggeration) as compared to the real deal, especially with BioShock Infinite as a direct timestamp game, but also thematic futurism of Fallout 3 or Fallout 4. I’ve discussed BioShock Infinite, and to a lesser extend the BioShock series more broadly throughout this series, but I think there’s something to be said about either series as an extension of digitization and adaptation — something I’d like to explore, at least a little bit, at the end of my final paper.

However, for now, I think one of the lingering things sticking with me is just how much a study of pulp magazines continues to draw through to contemporary analyses — especially after surveying half of the class’s rough drafts last week. Pulp magazines are alive and well, in some way or another. While I focused on SF two weeks ago, many genres were adapted and created through pulp experimentation (although it is perhaps unsurprising that there were a great number of flops too *cough* looking at you Basketball Stories *cough*). In general, it was a really innovative time, seemingly filled with possibility and growth (which unfortunately would be burst through the Great Depression). New and exciting futures were on the horizon, or at least that was the message being sent. Sound like anything else you know?

In considering the start of pulp magazines, including its boom and its bubble burst, I can’t help but think of the early days of the internet.

Although we don’t refer to it as the “World Wide Web” anymore (at least, I don’t think we do), I remember when the internet was TheInternetTM. This hugely new and innovative medium, taking households by storm. Inspiring movies (You’ve Got Mail, anyone?), connecting people all over the world, spreading information, allowing for user-generated engagement…The more I talk about it, the more I wish I had written a paper comparing the history of pulp magazines with the history of the internet, up to and including a general lack of support and academic interest to its “low brow” elements. Oh well, another paper (or blog post) for another time. Suffice to say, once the parallel is made, it’s hard to shake off.

I remember being excited for our first dial-up connection. I was lucky that my parents were always particularly technologically advanced and I had ICQ from a very early time (I’m pretty sure circa 1998). I built webpages on GeoCities through code I learned from UW’s Arts Computer Camp (while stylishly pulling off my own play-performance of Sailor Venus at the end of the summer). I practically learned how to type (at least as fast as I do now) by spending far too many hours typing out conversations on Yahoo chatrooms and games. I mean, I was there, I was invested, and my life was forever changed because of it. I can only imagine, in some way, that this is how the boom of pulp magazines felt. A rush of new technology, new and readily available information, connection, engagement.

It’s all there (and now I wish I had chosen to write a pulp history story version of the dawn of the internet…so many ideas, so little course time left), and it’s astonishing. I’m sure even in some way, people felt like this at the early years of the telephone, the printing press–at all major technological changes. So I wonder how much of our study of pulp magazines is about the technology as well. Not that we haven’t discussed this in class, but I think it’s an area we haven’t explored as much as we could (again, only so many hours!). Even the act of digitization, of bringing pulps to the internet, is another link in that chain, tying it all together (brainblown.gif).

In the end I think, people just keep looking for a way to connect with one another. From cave paintings, to Snapchat, and everything in between. Pulp magazines were a way to convey culture, to control culture, and to express counter culture. They were what people made them to be. As the internet is now, and as something new and distant in the future will replace, they are equally important as part of human history and communication.

In archaeology we’ve come to learn to treat peoples of the past as just that, people. “People have always been people” as it were, and their cultural artifacts reflect the agency of once living and breathing people. If we take that to be important, as we take anything we do today to be important (except maybe fidget spinners), pulp magazine’s value should be clear.

Where there are artifacts, they are fossilized evidence of peoples’ action in trying to intervene in history…Artifacts are a testimony of context, not resolved social structures. (Wobst 47)

What will our legacy be? What will our cultural artifacts have to say about us? Maybe future scholars will academically analyze the importance of our memes. Or maybe, it’ll be something altogether different.

Either way, I’m left with a lot to think about.

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

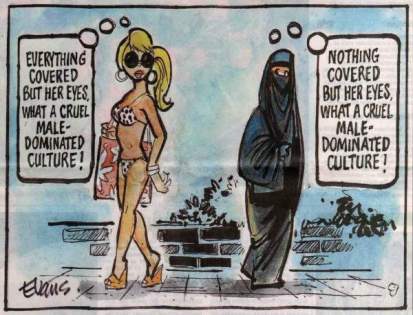

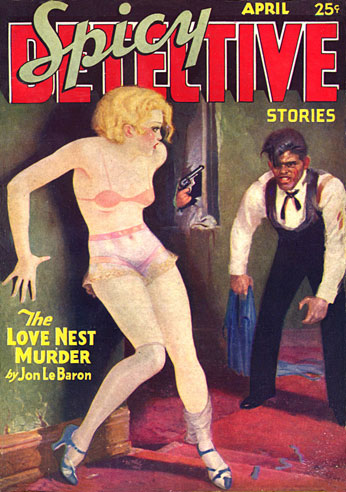

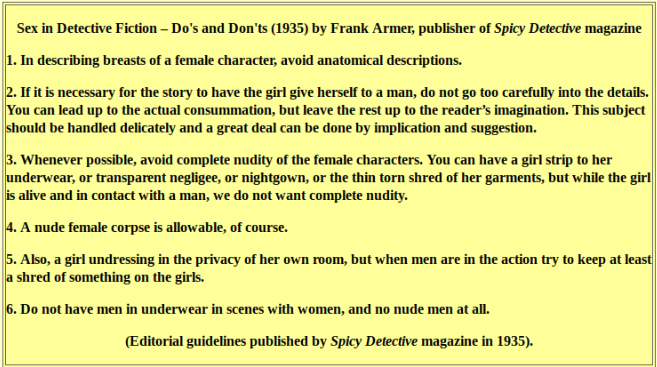

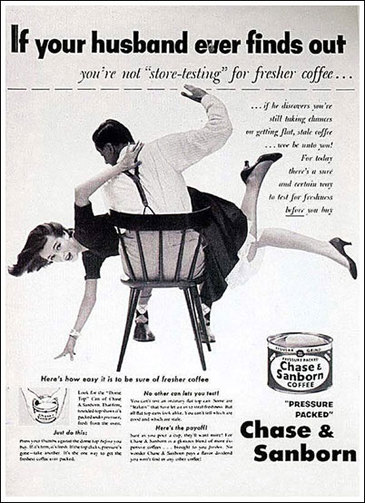

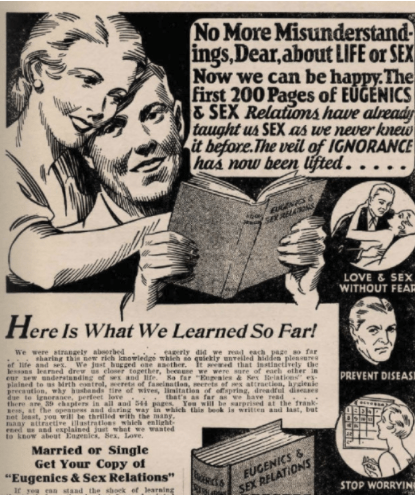

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?

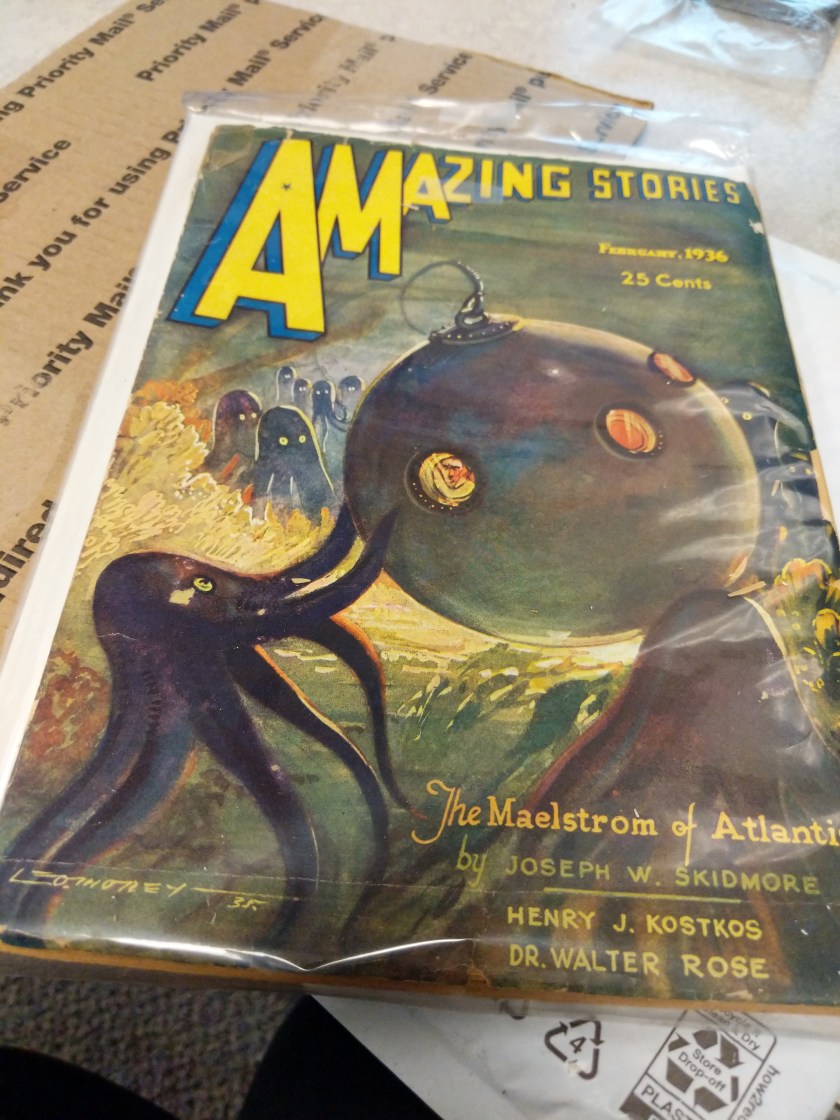

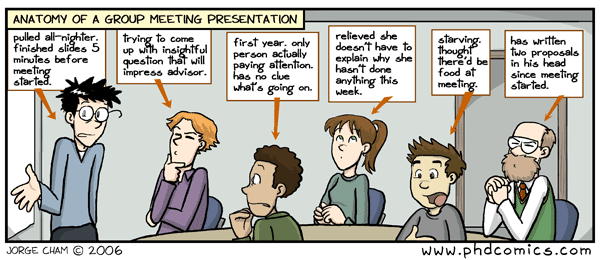

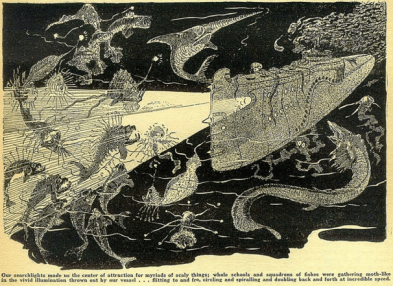

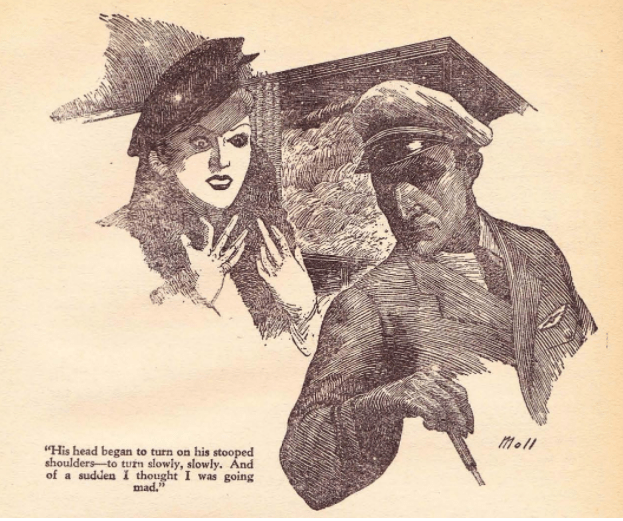

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever. I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,

I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.