Over the past few months in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, I can’t help but feel like there’s been an increasing awareness paid to community. What it means to be part of one, how do we come together as one, how do we build one in an increasingly digital age?

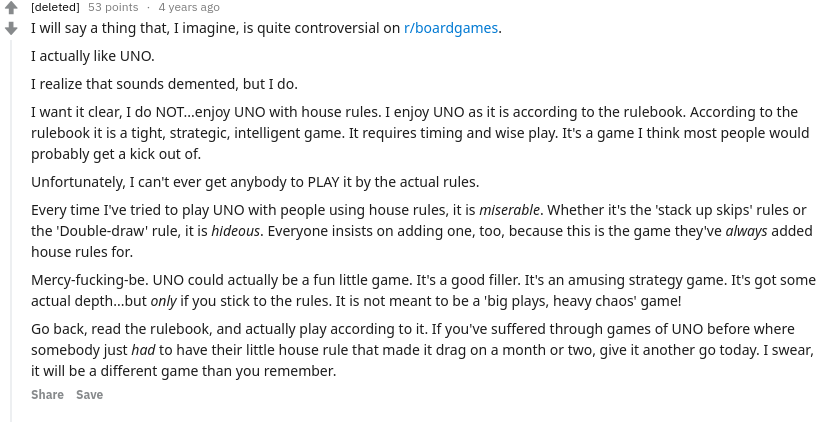

So many questions that people are now asking themselves as though they’re waking up from a haze. For so long people have been going through the motions of life and only truly living in the wisps of what community is supposed to be. People love to blame the internet and social media for destroying historical meanings of what it meant to be part of a community—but many of these people have ceased to evolve to see what modern day communities are actually like.

Then COVID struck. Slowly, then encapsulating the world. With the physical spaces we used to gather no longer being accessible, people fled to the internet to try and make whole the social spaces they were deprived of. The very people who claimed that these spaces were the death of all community are now struggling to try to figure out how to use the internet as the vast saviour of all things social.

Then COVID struck. Slowly, then encapsulating the world. With the physical spaces we used to gather no longer being accessible, people fled to the internet to try and make whole the social spaces they were deprived of. The very people who claimed that these spaces were the death of all community are now struggling to try to figure out how to use the internet as the vast saviour of all things social.

And yet, they still don’t understand.

Now that I’ve passed into the post-comps-dissertation-writing-I-swear phase of my PhD, it’s hard to not see things align in an eerily timely and useful way. While I write about gender and power dynamics for my dissertation, I’m effectively writing about how communities are built and developed online. How their ideologies are developed and perpetuated; how we make meaning in digital spaces. As my academic mantra has been for a while: People, Technology, Culture.

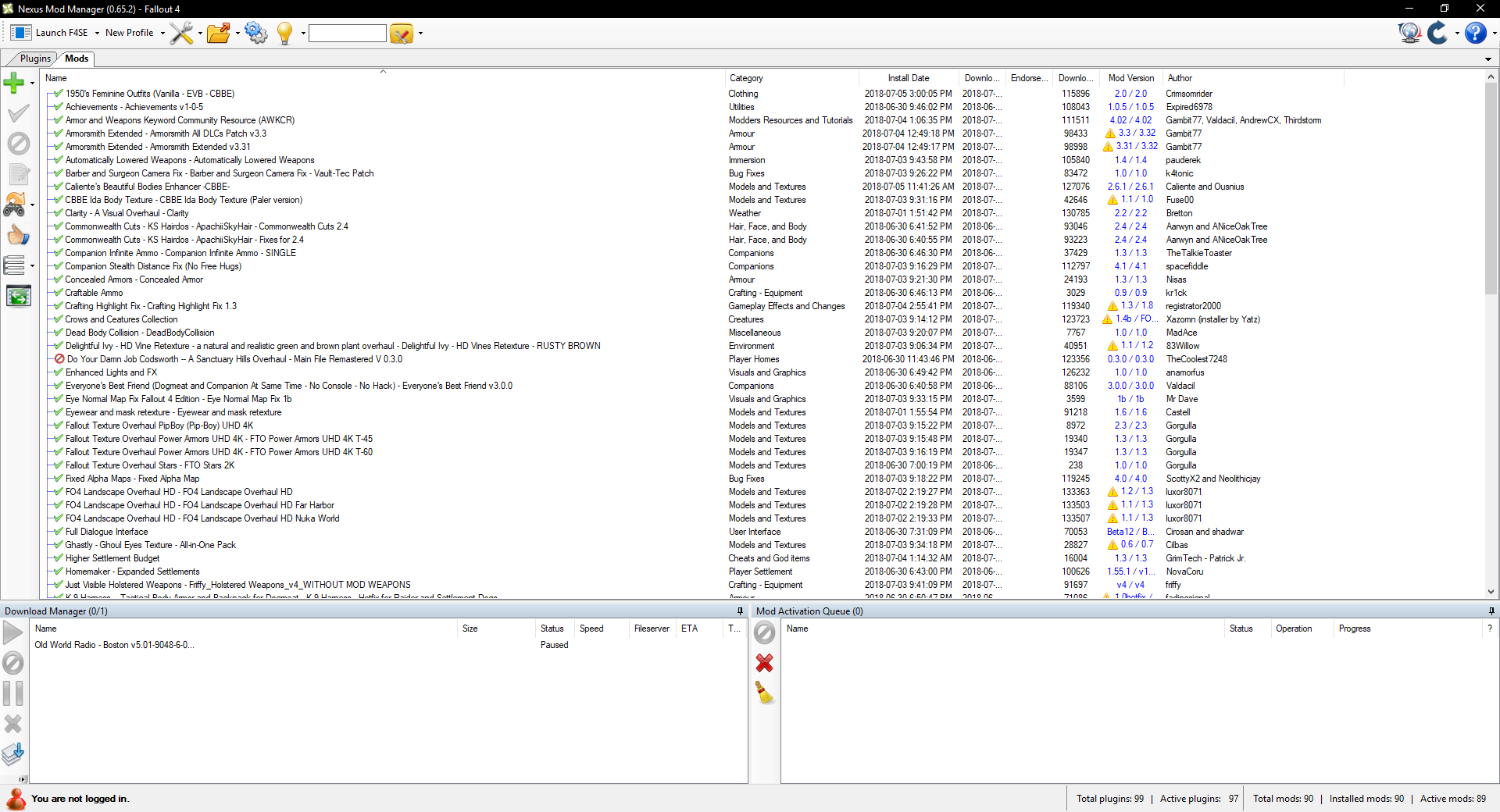

I’ve had the pleasure of receiving a series of graduate research scholarships to develop a community for the UW Games Institute from the ground up in a digital space—predating the COVID epidemic, but accelerated in kind by its appearance. I’ve had in-depth experience with thinking through how to build the culture we want to have, and how to reinforce the culture we already had, through an entirely virtual medium.

This has given me new perspectives not only on how simple it can be to consciously choose the framework you want a community to develop around, but equally how easy it is for people to overlook the simple things that can easily breed discontent and toxicity if overlooked.

As per usual, this is going to come back to World of Warcraft (shocker, I know). I spent the morning talking to my current GM of HKC, whom I’ve known for over 13 years now. We talked about our community, the world of gaming culture, and most notably, the recent scandal with Method.

This scandal sadly has come at no surprise to me, as one who researches within and participates heavily in the competitive gamer world. The stories relayed through this news blast aren’t unique—in fact they’re far more common than many want to believe—but the more these stories come to light, the more…hopefully…we’ll come to see a change in the gaming “community.”

I’ve been lucky that I learned to navigate these worlds earlier, and have surrounded myself over time with people who support the kind of virtual space I want to be a part of, but many aren’t so lucky. That spine, was an important part of my conversation today. We have a strong and long-lasting community within Hello Kitty Club. But despite our size, we aren’t free from risk of drama (nor have we not had our share of it in the 10+ years I’ve been a part of its leadership).

What struck me today was the willingness to work towards creating systems to stop, acknowledge, or offer recourse for situations in the same wheelhouse as what happened with Method (and others) before they even start. We aren’t some international gaming juggernaut, and yet, the importance of creating safe spaces for all members of your community, is no less important to us.

Over the years, there’s a reason why people keep coming back to HKC. Many guilds rise and fall. People disappear without a word. But for some reason, people keep coming back to us and remember us long after we’ve parted ways (or changed servers), and I can’t help but keep coming back to the question of community. We’ve evolved over the years but there’s something about our core, our attitude, our values that seems to strike a chord with people. Something we hope to soon put to writing to ensure that that energy can continue to thrive beyond the current leadership.

I mean….let’s face it, we might leave this game eventually right? (*awkward laughter*)

In the meantime though, I’m proud to be part of who HKC is today. We acknowledge our own missteps in the past but equally are learning from them in order to build a better community in the future. Even if it’s just in our one small corner of the Discord & Azeroth universes.

#GamerGate, Tech industry sexual harassment leaks, #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and through this current Method scandal. All of these things happen everywhere, across the globe, but they are changed systematically at the small community level.

We work together to fight intolerance and misconduct at a local level and it can have a rippling effect that spreads across the whole of the industry. It’s human nature to gravitate towards what others are doing successfully. We must continue to fight, no matter how helpless it may seem by learning about these big-news items.

All news is local news, and the biggest of scandals start with the smallest of problems.

Build your communities with care and you’ll see them grow. Let them populate unchecked and you’re just setting yourself up for disaster. I’m sure Method meant well, but at some point you need to let go of old ways, evolve, and stand up for what’s right.

Change is an individual choice. Choose to build better communities, adopt more inclusive values, choose to listen to others.

Choose a better future by acting as though it were already here.