I guarantee that no two User Interfaces in World of Warcraft will be quite the same. Both WoW and The Sims have notoriously supported modification to their videogames over the years, even going so far as to convert existing addons or mods into actual features of later gameplay. Where they differ greatly however, is their stance on cheating.

While it might be front and centre on their website now, The Sims franchise used to have its own share of community shared and pseudo-mythological cheating console commands in circulation. While they were never so obviously discussed by the developers, the existence of easy-to-remember codes like “rosebud,” “kaching,” or “motherlode” for more money, always seemed to suggest that they were ‘in the know’ in giving these tools to players. Further still, there are plenty of things that the early entries to the franchise required you to do via console command, such as stopping aging, that are now features in the normal ‘settings’ of The Sims 4.

Cheating is a big part of the game. Not only is it easy to access, but it’s even something we kinda, sorta, actually encourage. Strap in as we show you not only how to cheat in The Sims 4, but tell you a few of our favorites The Sims 4 cheat codes (EA, The Sims 4)

Can these kinds of cheat codes even be considered “cheating” if they’re considered an endorsed part of the gameplay? Rather than allowing for extra lives or level skips through an implicit playtesting model, EA has gone one step further and condoned the use of their cheats as an active alternative to play. By so doing, they are acknowledging a number of ways for players to consume their content, and allowing people to use it as a building or design sim, rather than just for playing house. Further still, the game doesn’t penalize you for using cheats of any kind, and achievements in the game continue to record as they would if you never typed the [`] key at all.

Their endorsement of cheating comes alongside their in-game promotion of modified Sims and Lots (houses/businesses/community, etc.) through the Community Gallery. Practically since its inception, The Sims generated a very active modding community. They’ve been the source of providing new hairstyles, clothing options, furniture, houses, meshes, and a whole load of features before the game developers themselves included them. For example, the modding community already had versions of cat and dog companions (within a very limited vein) before an official expansion was ever released to include them. What we have to consider alongside this seeming embracing of “cheating” and “mods” within the native client of The Sims 4, is that the company is attempting to exert control over its modding community.

When a mod system is detached from the game itself, any number of issues can arise, both for the company and for the player. The players could run themselves the risk of downloading harmful files or corrupting their game beyond repair. The developers on the other hand, may risk financial loss over user-created content that mimics things they’d otherwise charge you for. In the end, by including a community gallery within the game itself, EA encourages its players to pay for the game itself, and its expansions (the gallery is not available through pirated versions), as well as discouraging players from reaching beyond their borders for content, via sites like ModTheSims or TheSimsResource. Despite efforts to contain the modification of The Sims, sites like these continue to prosper, providing content to the community where EA and the gallery cannot.

If we go way back, this design philosophy has almost been with The Sims from the beginning, and it seems to me that these kinds of cheats are not really cheats at all. User driven content and world-spontaneity has always been a desired feature on The Sims‘ horizon. Back in 2001, the Game Studies journal conducted an interview with Will Wright at Maxis, aka the mind behind The Sims, SimCity, SimAnt, and more.

While this interview was conducted before the failure that would-be The Sims Online, a sim-universe MMO, Wright shared some interesting insight into what his view of the future of the franchise would be.

I would much rather build a system where the players are in more in control of the story and the story possibilities are much wider. For me the size of the space is paramount. Even if it was between the player controlling it or it being random, I still would want larger space in either case…Because I think you could always make the possibility space larger at the expense of the plausibility or the dramatic potential, or the quality of the experience. There’s probably some relationship between the quality of the experience and the size of the possibility space. So we can make the possibility space huge, just by giving the player a thousand numbers. And “Here, you can make any one of these thousand numbers whatever you want it to be.” That’s a big space. It’s just not a very high quality experience. So we start wrapping graphics, sounds scenarios and events around those numbers, and we’re increasing the quality of the experience you have. It has more meaning to you. In some sense it becomes more evocative. You can start wrapping a mental model around that, as opposed to this pile of numbers (Pearce).

The Sims was never supposed to be just about what stories Maxis (and later EA) could tell you, but rather the stories you could tell yourself. Part of this meant allowing for as broad of a ‘possibility space’ as the code could provide, and where those borders could no longer contain the possibility, the community took over instead. In this way, The Sims in principle can never be modded or “cheated” too much to be considered failure. The inclusion of these things from the game’s very design philosophy presupposes that we might not even have a word for their use within the game’s system. As much as it’s hard to call endorsed “cheating” cheating, it can be equally hard to call inclusion of hairstyles, clothing, or furniture mods, when they fulfill the game’s ‘prime directive’ as it were: enhancing, or even ‘extending,’ the possibility space and user experience. Perhaps “extensions” is more appropriate in this case. “Players of The Sims 2, like players of the first version, have found that one of the most gratifying aspects of play is sharing unique objects with other players. For example, in just under four months (September 2004– February 2005), Sims 2 players created and uploaded more than 125,000 characters and houses to share with others” (Flanagan 50). If The Sims is just about playing house (Flanagan), the only limits ought to be those of your imagination, and as long as the community is willing and able to push those limits, all extensions and cheats are effectively working as intended.

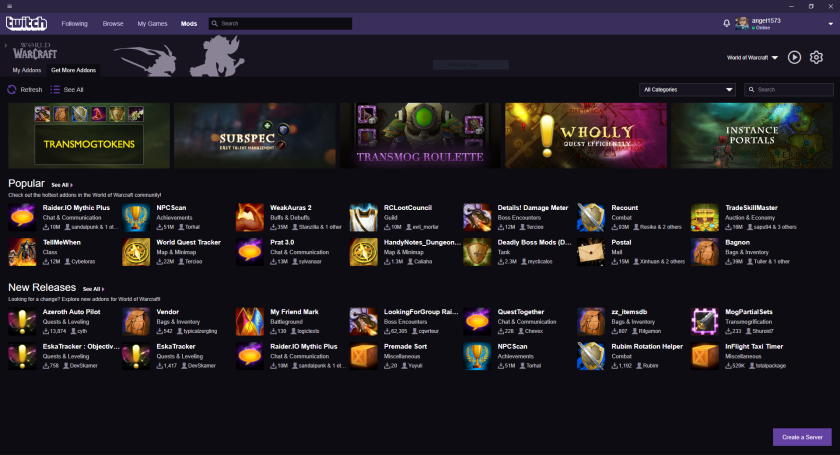

In contrast to The Sims’ stance on cheating and modification, World of Warcraft and other similar MMOs have a much heavier hand. Mods in WoW toe a very fine line between acceptable usage and bannable offence. Generally over time, Blizzard Entertainment, developers of WoW, have taken strides to limit what mods can and cannot do to their game in order to limit how mods can help (or hinder) player experience. Where The Sims is about expanding one’s possibility space via cheats and community content, WoW is about delivering their content through a myriad of lenses, so long as it doesn’t give any one player any significant advantage.

As WoW is a web-based always-online game, with achievements, the need to control cheating is paramount and judged accordingly. Even if a mod ‘arguably’ only affects your experience, like hacking the visual skins of your characters on your game files alone, could be deemed a bannable offence (as happened to a guild member of mine back in The Burning Crusade expansion). Along these same lines, however, while there are no mods allowed that give a significant advantage to one player or another, the community (particularly in high-end raiding or PVP situations) has deemed a number of mods indispensible or effectively required in order to proceed through the “stock” client. Many of these ‘essential’ mods are aimed at modifying and improving user-experience for more difficult content. Mods like “Deadly Boss Mods” (DBM) or “BigWigs” give players access to boss timers, debuff and ability announcements, and often even player cooldown notifications while facing difficult foes in large groups. This kind of information is argued to be indispensable, and yet, is not something ‘truly’ included in the base files of the game. While bosses tend to give visual or audio clues to when they’re about to slam in front of them in a frontal cone, the average player believes they benefit from having DBM on their side to give them a 10 second heads-up.

Like The Sims, WoW‘s mods are user and community driven. But unlike The Sims, it is not the existence of the mods where the community ends its say, but rather in WoW, it is only the start. Alongside DBM, other mods for average user experience are often touted as being essential, features that change your action bars, your bag space, your interaction with Mission Tables, your party information panels…even your outfit management. While many of these mods have worked in concordance with WoW’s stock user interface, I have heard many player say that they struggle to play the native client without their mods. Even when Blizzard has incorporated a version of the mods “Outfitter” or “Grid” into the basic UI, there’s always something “off” about them, and it can be hard to acclimatize. When hearing that some players play with the stock UI, aside from ‘essentials’ like DBM, players often scoff and ask “if they still have auto-attack keybound as well.”

Installing mods in this way is observed by the community almost as a rite of passage, essential not only in what needs to be downloaded, but that something has to be downloaded at all. And unlike The Sims, all mods are governed outside of the Blizzard umbrella, currently governed primarily through Twitch (formerly Curse).

What the WoW example asks us, however, is how much of a game has to change before it ceases to be the original game? In this example, Blizzard limits what can be done with mods enough that the game is required to stay more or less the same in terms of narrative and basic interaction on the live client. What changes is how people interact with that world. It remains to be seen whether or not that qualifies as a different game for every version of a UI that players look into Azeroth with. Whereas The Sims retains its identity not by being scrutinous of how the game is changed, but rather that the game is changed at all. Although both modding and cheating exist within both games, neither one changes what the game is at its core, and thus, arguably, the game is “preserved” despite them.

As we will soon see however, this is not the case for all games and modifications. Onward to Bethesda, and the modvolution.

Academic References/Further Reading:

Flanagan, Mary. Critical Play (2009).

Pearce, Celia. “Sims, BattleBots, Cellular Automata God and Go: A Conversation with Will Wright.” Game Studies (2001)

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

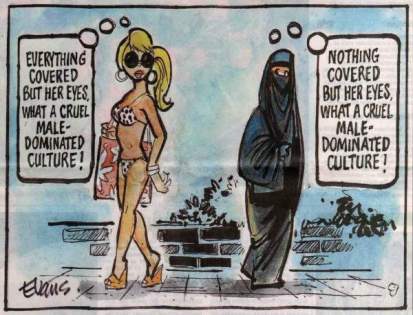

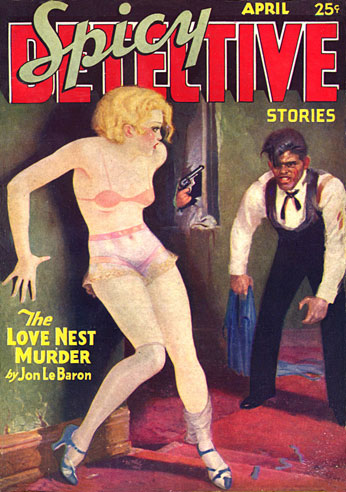

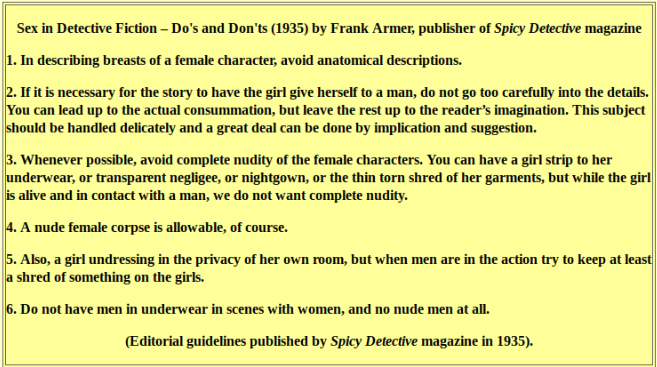

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

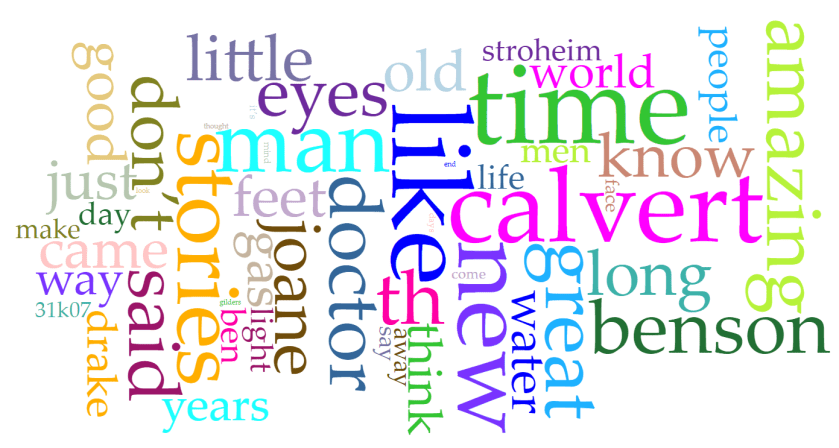

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?