If you’ve even dabbled into the discussion of gender and history, you’ve more than likely stumbled by a mention of a lack of female representation in the documented past. It’s something that’s come up in pretty much every course that deals with the past throughout university. Documentaion of women’s affect and even their presence in history is lacking because they just weren’t the ones who were writing it down.

Well, that’s not entirely true. Women were writing, and they were participating in documentation, but not quite as much as their male colleagues. Additionally, it was only usually women of power or money who had any time or ability to write anything at all. We see this even as early as with Sappho, the ancient Greek poet. She was a wealthy citizen, and as a result, had the privilege to leisure time and thus was able to write. While there are very few documented female voices in history, there are even fewer of the average women who would have lived alongside their much more represented male counterparts. Even when women may have written their perspective, carved their story, or have been celebrated in their time, historians have traditionally washed away female participation from the record. Anything which presents women as vocal individuals in their own right, in their own lens, detracts from the male domination narrative you see.

It’s not all that cut and dry, however, as there are plenty of women’s studies and history classes to teach the messiness of such a subject. Where we can tackle however, is something that we discussed in class this week, namely the male-washing of the Western genre. While industrialization allowed for more and more women to gain access to reading and writing, the legacy of their participation in the literary market would go overlooked.

As we discussed in class, the Western genre in its earliest days, when looking at the pulp magazines themselves, had high female engagement. Not just in reading either. Women were writing stories too. While scholarship on Westerns focused on literary sources, skewed towards male authors, the truth remained that the Western genre developed through simultaneous and mutual involvement in the genre. It’s no surprise that in the 1950s and 60s, eras desperately trying to embolden gender roles against an influx of new thinking, that scholarship would erase the presence of female participation. Naturally, it would seem to them, women would have come to the genre only for the romance. Women didn’t want to see the guns or action stories, nay (or perhaps neigh), they only wanted to read about stories where subservient (or perhaps wild-then-tamed) women fall in love with dominent men and start a new life in the West. They couldn’t possibly be interested in the same “men” stuff *insert chest bump here*.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever.

I regret that I’m getting fired up about this more than I intended to, but it strike a chord with me. I have, thanks to my training through a very forward-thinking parent, I’ve always grated against imposed gender roles. Why should boys get all the fun stuff? Women have always been interested in things beyond romance and beautification, but because gender roles (albiet ever shifting) shame them for it, they either train themselves not to be interested, or find an excuse for something societally acceptable within them to like. It makes me hurt, not only for contemporary audiences and issues, but also for the women in history who have had their voices silenced or ignored–or worse yet, attributed to a male counterpart. There is a place for everyone in this analysis, in this field, and it’s up to us to go back and return life to those who we can find within these pages. To give back credit where it is due, and to change scholarship on history to better represent the truth of gender (and race) participation.

I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama, abuse, artificial intelligence, ethics, free will, and consumerism (alongside so much else), against a backdrop of stunning visuals, breathtaking sets, and a moving score. It’s a show, for me, which proves that Westerns can be for everyone (well, except maybe not kids in this case). I can only imagine, that in the age of pulp magazines, a well written Western would have the same effect on its audience as Westworld has today. A good story need a blend of a variety of elements, and the best way to accomplish that would have been to incorporate blended perspectives and angles into a magazine.

I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama, abuse, artificial intelligence, ethics, free will, and consumerism (alongside so much else), against a backdrop of stunning visuals, breathtaking sets, and a moving score. It’s a show, for me, which proves that Westerns can be for everyone (well, except maybe not kids in this case). I can only imagine, that in the age of pulp magazines, a well written Western would have the same effect on its audience as Westworld has today. A good story need a blend of a variety of elements, and the best way to accomplish that would have been to incorporate blended perspectives and angles into a magazine.

If for nothing else, the lesson of male-washed Western genre scholarship calls for us to use a critical eye when looking at other pulp magazine genres, as well as literature more broadly. Just because it’s not obvious, or its been overwritten, doesn’t mean female voices aren’t there–that female participation isn’t there. Sometimes you just need to dig a little deeper, find meaning in the blank spaces, and help to try and uncover what history has tried to erase. We cannot hope to move foward in our own scholarship, if we continue to accept ingrained and perpetuated biases about the people we study.

The cycle has to end somewhere, why not with us?

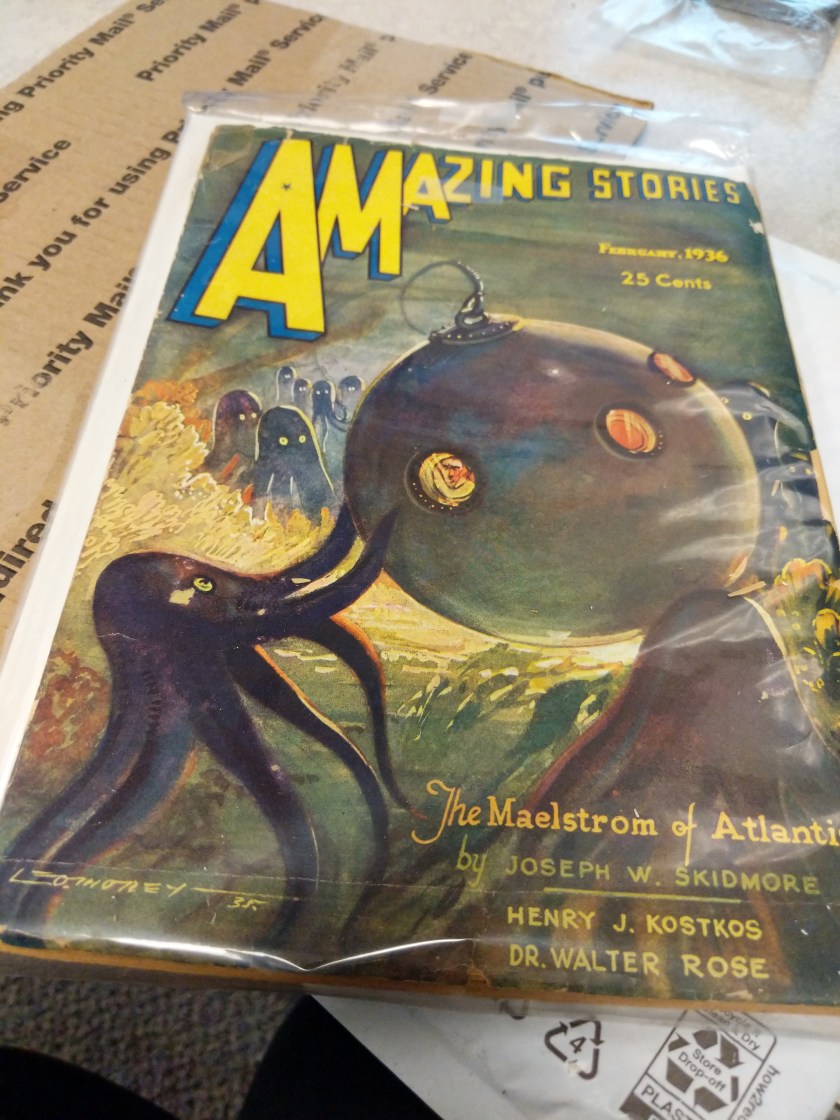

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.