Along with the idea of fairness comes its necessary complement: cheating. Cheating is what someone does to give him/herself a more than even chance to win. At least, that’s what we most often call cheating.

When I happen to notice you attempting to draw universal attention to my little cheat, I am aware that the motivation for your sudden intensity stems not as much from your concern that I have broken a rule as from your feeling that I have somehow deprived you of your opportunity to win…

It is obvious that your concern with my cheating is biased in your behalf. If I’m doing something wrong, even if I’m in flagrant violation of the rules of the game, as long as you perceive yourself as winning, everything’s cool (Koven 24-25).

To what lengths will you go to win, to succeed, to overcome the technical rules of whatever game you’re playing to get a little bit of an advantage? Would it make a difference if the game enabled you to accomplish this task via embedded cheat codes? What do we make of sanctioned cheating vs. unsanctioned cheating? What if you don’t even know you’re circumventing the rules-as-intended?

When playing board or card games with friends, we already know the routine. Often “house rules” need to be established alongside “legitimate” ones, because we seem to have a predisposition to change games as they’re presented to us. We demand that our friends and family reveal their house rules before a game even begins, lest we find out mid-way through that people are actually not on the same page. What happens when you land in free parking in Monopoly? I’m sure we’d be very divided on the answer. “Wait, that’s cheating!” we’d be inclined to say, when our peers reveal themselves to be playing an entirely different game than us, while all looking at the same board. Some strange parallel reality where someone jumps up and stops you from buying a house on your second pass of “GO” in Monopoly.

It’s not surprising that this was a heated conversation in the board games subreddit, and spawned at least one thread trying to spin the ‘positivity’ of house rules. These are things we usually only find in board and card games, because (without mods or hacking), in video games, the code simply doesn’t allow us these affordances. This is thanks to Procedural Rhetoric, where game philosophy and developer ideological visions are written into the very laws which govern how the game operates. For example, when playing UNO on the Xbox 360 (or other ports), the kinds of house rules faced by this unfortunate redditor would simply not be possible.

The code would prevent such frustrations from occuring in a the videogame version of this card classic. Even when “house rules” are allowed, they’re usually custom-made and allow only for people to enter into the game acknowledging them in advance, with no room for mid-game shifts in playstyle. Even custom games in more recent first-person shooter titles like Halo or Overwatch, lay all the custom rules upfront–people know what they’re getting into. At all stages of these custom maps or games, players are often required to choose from what the developers have already accepted as “sanctioned” deviations from the norm.

This idea of customizing game rules and house rules within board games and their video game companions brings us closer to the question of what it means to cheat in games. The implementation and adaptability of board and card game house rules are perhaps more complicated than a handful of blog entries can address, but, I think we can safely look at why and how we cheat in our games through looking at some specific videogame history and case-study-style examples via the following series:

- The Legacy of Cheat Codes & The Game Genie.

- What makes us cheat?

- Hitting the “Motherlode”: Cheating/Modding in The Sims & World of Warcraft.

- Haecceity: How much modding before the original game experience no longer exists?

Academic References/Further Reading from the Series:

- Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games (2010)

- Flanagan, Mary. Critical Play (2009).

- Isbister, Katherine How Games Move Us (2016)

- Juul, Jesper. The Art of Failure (2013)

- Koven, Bernard De. The Well-Played Game (2013)

- Pearce, Celia. “Sims, BattleBots, Cellular Automata God and Go: A Conversation with Will Wright.” Game Studies (2001)

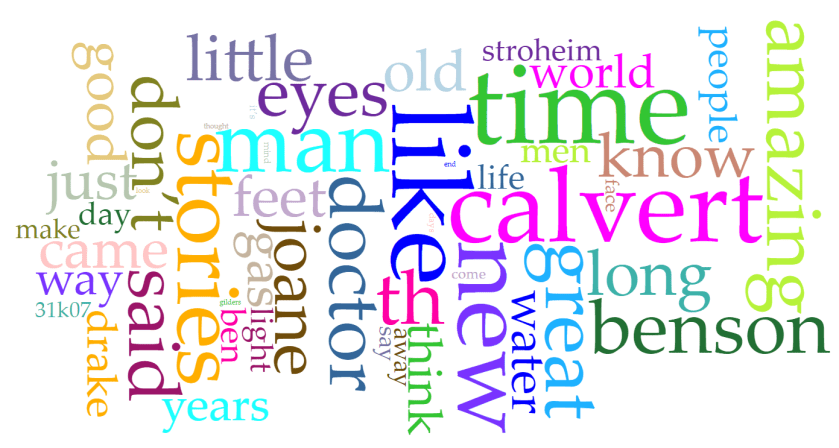

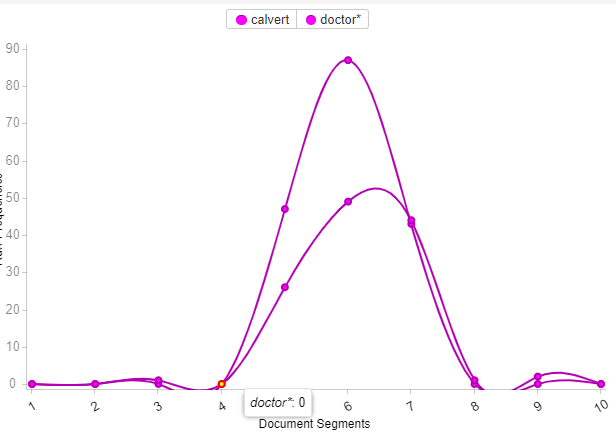

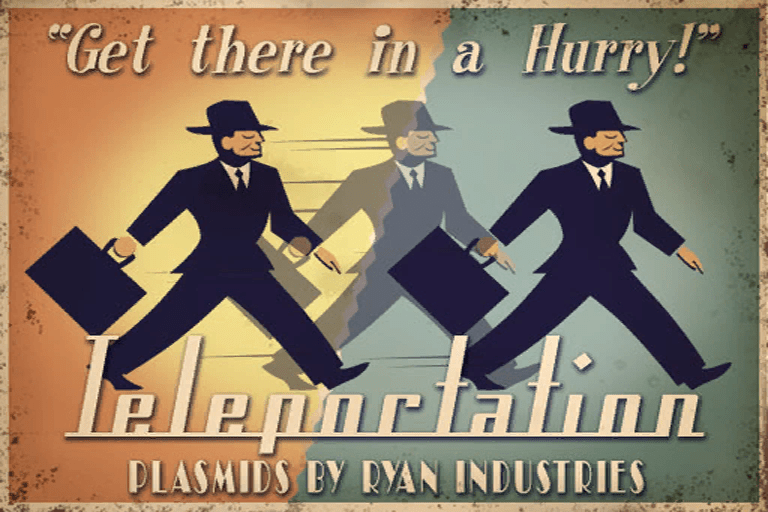

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

One might argue that any genre could have been created in this way, which is true I suppose, but SF latched on at the exact right nexus of context to blossom into what it became–further evidenced by how much SF developed after Amazing Stories gave it a label. We see the first SF film

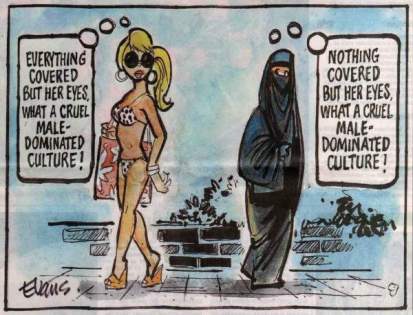

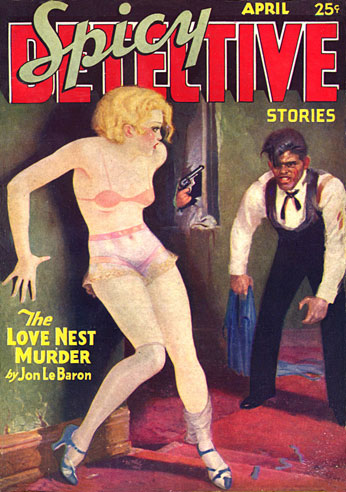

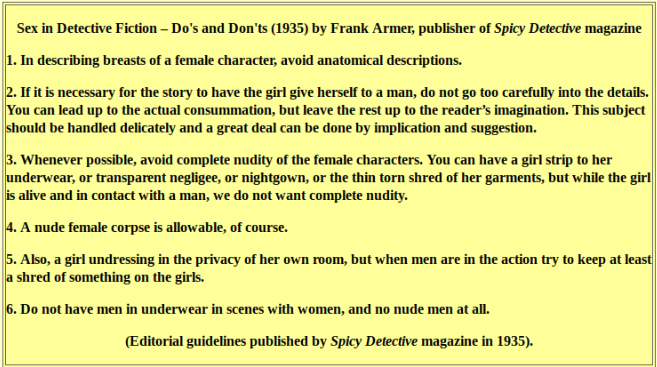

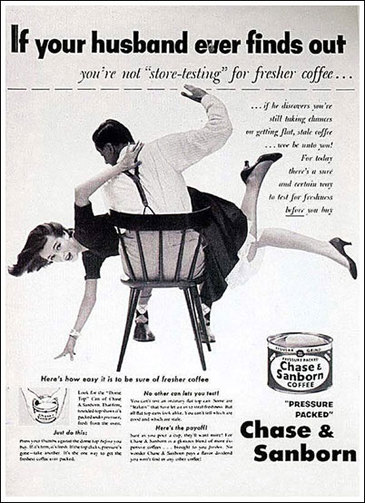

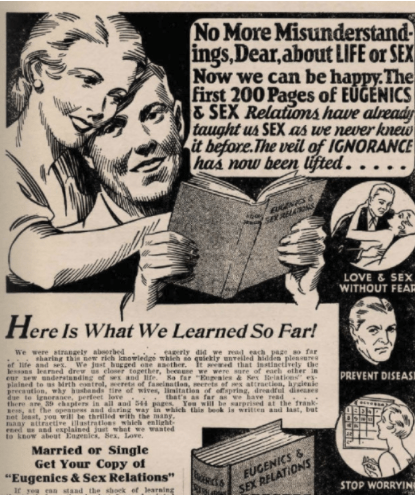

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

Today is International Women’s Day, and I cannot fathom closing out this post without briefly mentioning the looking glass mirrors of gender roles in pulp magazines. That being said, I’ll be brief, as I’ve talked about gender roles briefly before.

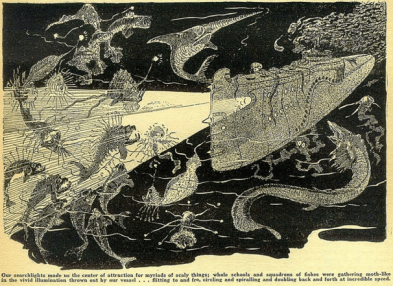

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?

Ultimately, this experience allowed me to reflect a lot on what it meant to read a pulp magazine, but also to read aloud in a group at that time. While I nearly lost my voice (and in truth my throat hurt the day after), I wondered if such a thing would have been passed around in a family setting to prevent such a thing, or if voices would have been accustomed to longer periods of reading at that time. Would pictures have made it more engaging for my audience? For any audience? How would have ‘city folk’ reading this story related to the tales of the wild west?

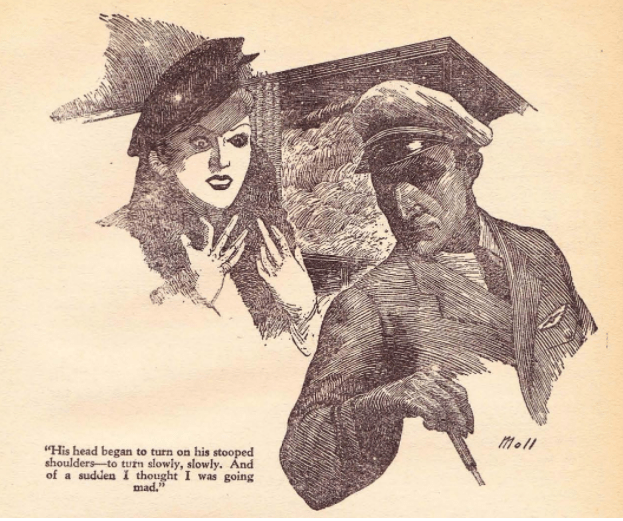

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever. I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,

I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,