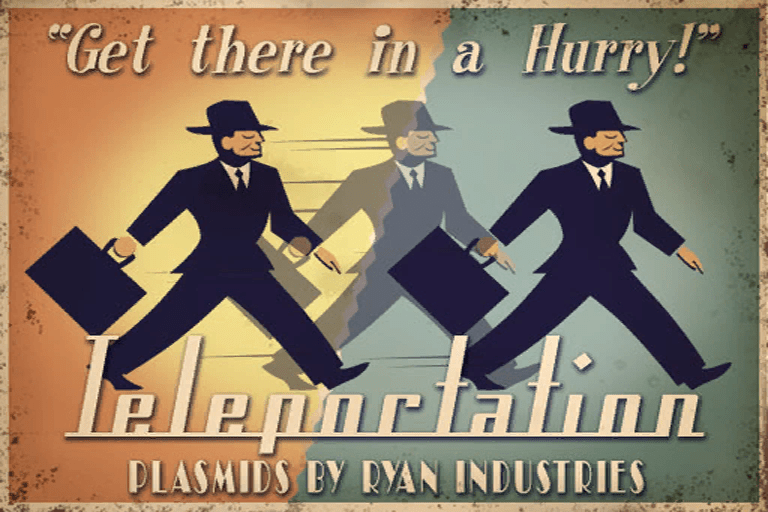

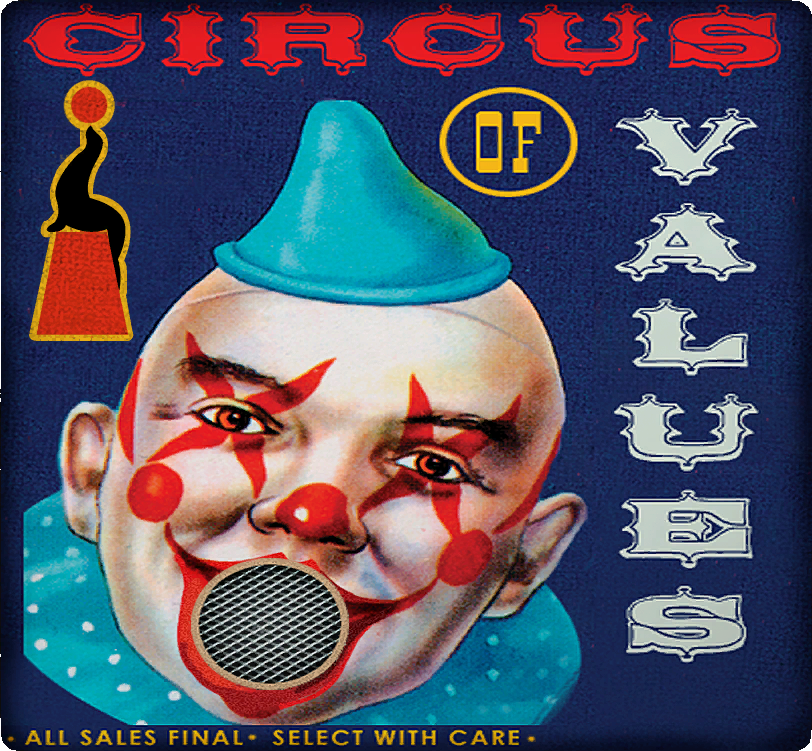

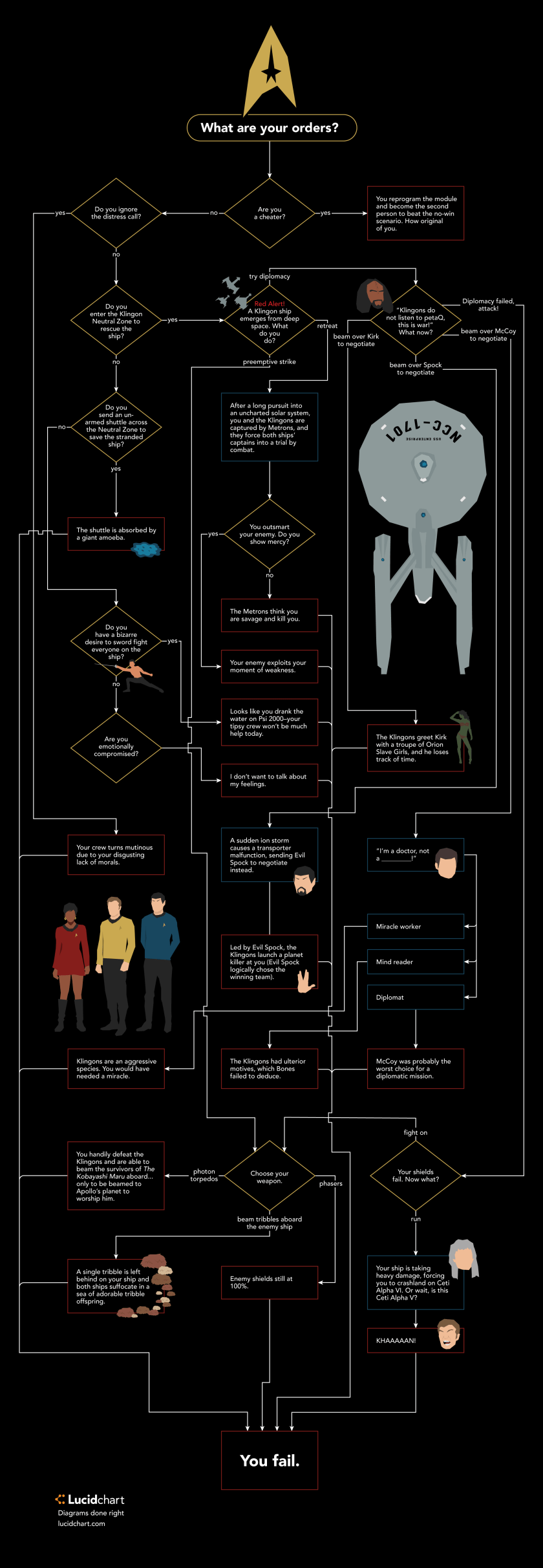

When discussing pulp magazines, I can’t help but come back to the BioShock series. Further still, when discussing advertisements. The title and featured image of this post naturally then, comes from a vending machine found in the original installment of the series. While there are equivalent machines in BioShock Infinite, there’s just something particularly accurate about a clown selling you medicinal aids and incendiary bullets that reminds me of the absurdity of advertising.

This fragment of the game’s contents encapsulates so much about advertising and capitalism which mirrors our discussions about advertising so well. “Get back when you’ve got some money, buddy.” The machine calls out into the void around it. The vending machine exists in a world where, among other things, true un-checked capitalism has taken over. The Circus of Values stands in more than just a place to buy items, but also where morality can be bought and sold. Something is wrong with you, and we can fix it with this product.

I briefly discussed in my first posting for this class, about the atmospheric choices of the BioShock series which really resonated with me when looking at pulp magazines. No area is more true than when considering advertising. The goals of ads, for the most part it seems, in the past century or so haven’t changed very much. While the wording or products may have changed, the message generally remains the same. We have a product that you need, and here’s why. While in some cases, this may take the guise of employment training (as is found in a lot of the magazines we’ve looked at), it also takes the form of products: ‘health’care, furniture, land, books, magazines, baby products, cigarettes, etc. These pages, that make the bulk of the beginnings and ends of mid-late pulp magazines, echo the sentiment of this Circus of Values. Spinning into a vortex of sales, it’s a freerange circus of what products you’ll choose to entertain this week. While the ads themselves may come across as the circus, trying to entertain potential buyers into purchasing (something that seems ever true with modern pop-up ads), I would argue that the readers too could be considered circus entertainers–buying products, buying values, to fit into the stage of society’s circus. Am I getting too deep? Perhaps I should buy more coffee.

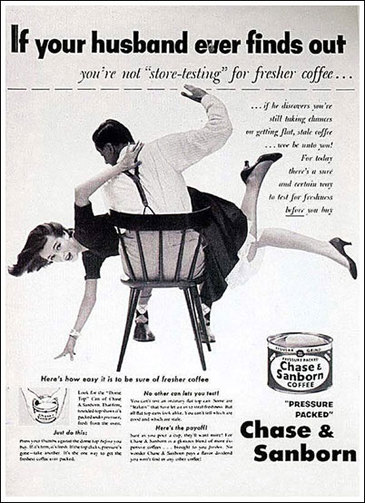

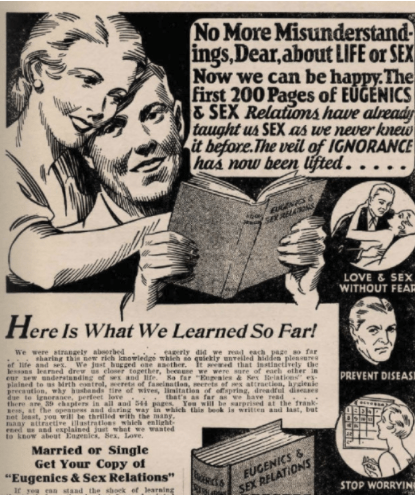

Of course, there’s an ad for that too. Advertising, like stories and other magazine images, exist to train people to behave and consume in specific ways. While we discussed in class early on that advertisements were often sold in bulk to publishing houses that produced a variety of pulp magazines, the fact remains that advertising still expected a certain kind of demographic from their purchase of advertising space. In this way, by deconstructing what magazines were published by which publishing houses, we can try to extrapolate what kinds of populations were targeted by these ads. While we can obtain small amounts of information about readership through analysis of “readership departments,” included in many pulp magazines, we can further try to compile an assemblage of facts by looking at all we have to offer, including targeted advertising markets. This kind of textual archaeology, gathering all the bits and pieces of the past to try to paint a larger story/snapshot of historical life, requires a lot of attention to detail, and demands scholars not to ignore anything.

So what kinds of advertising areas did pulp magazines try to provoke their readers into consuming? This week, we looked at an issue of Western Story Magazine, as well as one from Love Story Magazine–both published by the same publisher. Ads generally promoted, as they often do, striving for something greater, achieving more–through products. This included pathways to marriage, improved physique (for both men and women), financial stability, cooking prowess, and excitement (?). Most of these in some form find their contemporaries in current publishing and media. Others, paint a very specific picture of the lives people were being told to strive for:

As much as we can try to piece together readership from fragments like advertising, we need to be very keenly aware that advertising was more about who advertisers wanted the readership to be rather than who they were. Even the readership departments would have been heavily edited and curated to fit the ethos of the pulp magazine itself. Like so many other attributes of trying to piece together the past while living firmly in the present, we need to be careful about the assumptions we make based on what remains. If for nothing else, analyzing things like advertisements, or readership departments (which were effectively advertising for the magazine itself), help us to ask questions about the potential readership of a given magazine or publishing house. By taking as many perspectives as possible into account, we can try to get a more hollistic picture of the past. This of course extends beyond the magazines themselves, but also looking at other primary resources (periodicals, newspapers, literature) of the time, to try and find where populations intersect. Readers did not exist in isolation, nor should we treat them as such. Culture permiates everything, and somewhere beneath the layers of ads, stories, artwork, and news, we can try to find the remants of the people who held it all together.

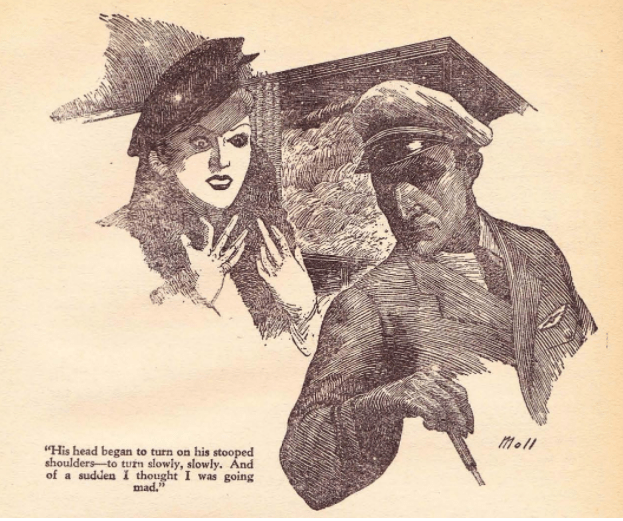

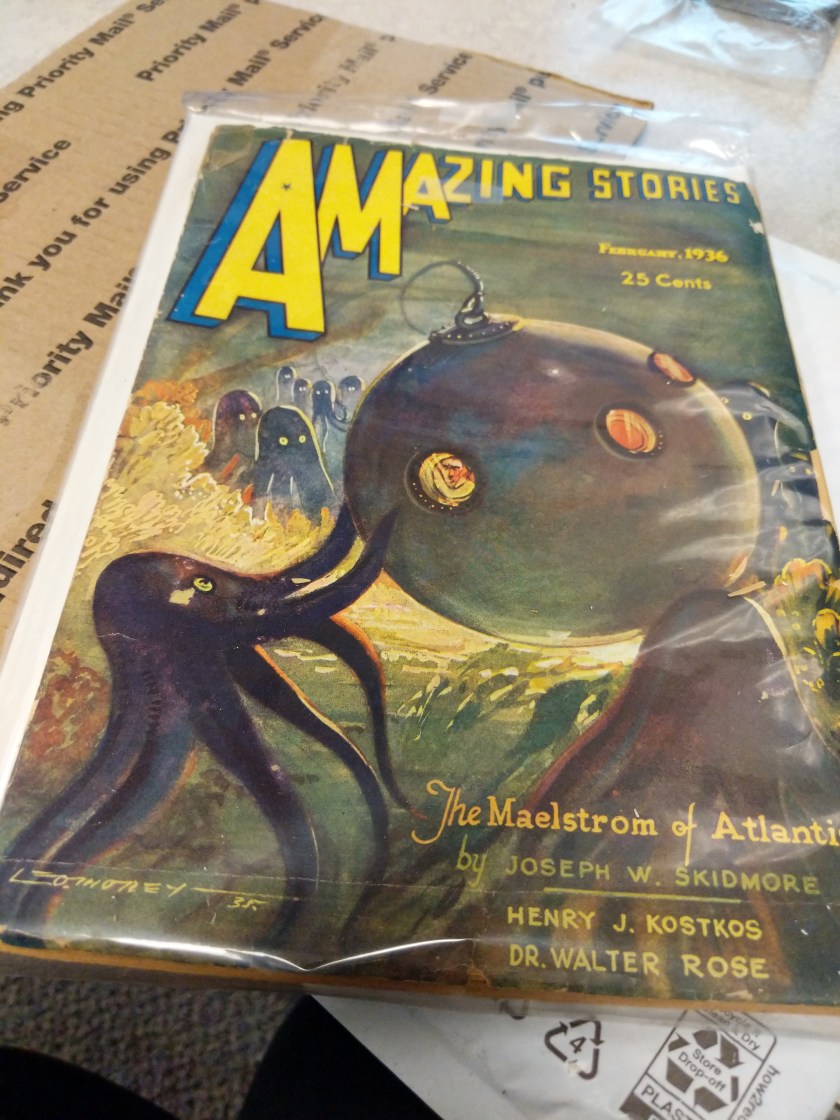

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

In preparing for class this week, I was struck by just how much my opinion of an image could change how I read or understood a story in a pulp magazine. While the image I chose to work on was relatively simple, it depicted a very specific climax of the story. I made note of what I could “read” in the image before actually reading the story, as well as a reflection after the fact. In truth, on its own, the image did very little to entice me to the story, but its inclusion gave me a lot of things to reflect on after the fact. Beyond my own analysis, I was even further impressed at how versatile such an image was for engagement throughout the class, as multiple people had chosen this image for their own analysis. While some of us struck the same chords, there was a lot of variation in how the image affected our individual perspectives.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever.

Does my sarcasm read strong enough? It’s so incredibly infurating as an academic to look back and be faced with misled and unfounded historical scholarship. We are now taught to look at the entire picture. To preserve all that we can about a text or an artifact, in hopes that even if we can’t analyze the whole picture, someone, someday, might. When faced with situations like this, one cannot help but be infurated by the scholarship of dominant male authorities, which changed official analysis of history to fit their own goals. Nevermind that the female-driven/written pulps lasted longer than their guns-blazing counterparts. Nevermind that the blended magazines came first. Nevermind that women had any active role whatsoever. I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,

I’ve visually referenced Westworld twice in this post–a brilliant TV show (which if you haven’t watched it, stop, drop, and binge it all right now), created by the joint efforts of a male and a female, produced by a female, and containing an amazing cast of strong-willed, well rounded, and well-written female characters. In the sci-fi/western/drama category, it’s everything an inclusive audience should want, and it’s no wonder it was critically recieved accordingly. It deals with complex issues of romance, action, drama,

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

A very à propos question to be sure, following our discussions from this week. What is lost in the digital preservation of pulp magazines? What is gained? We spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which scholarship and individuals could benefit from a database like the PMP. For my MA thesis I spent a great deal of time looking at archaeological artifacts and 3D replicas. In order to do this, I analyzed the semantics and meaning-networks of ‘originals’ vs. their digital replicas. While my thesis was focused on actual material replicas, I briefly touched upon purely digital replicas as well. Mass-access, availability, and production were all benefits to such a phenomenon. While not going into the ethics of digital replication (mainly of cultural objects you may have no authority to duplicate), I came to the conclusion that the benefits of digital reproduction and preservation outweighed the costs, at least for educational purposes. Most relevant to our topic this week however, I found that meanings and that something extra held within an original artifact only has meaning because we give it meaning. While something can be argued for seeing ‘the real thing,’ many people would not know any different if presented a reliably produced replica. While the old must of a vintage pulp magazine may be hard to duplicate, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were propmasters who could come up a solid approximation for the layperson, which would be indistinguishable, save for perhaps having them side by side.

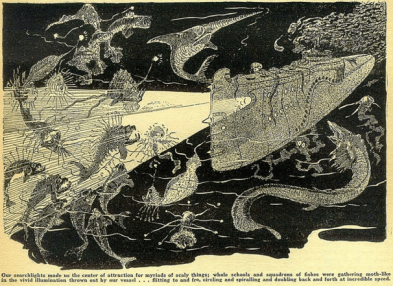

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.

In this early pulp magazine we found a steady theme of adventure…but only so far. Quite frequently the stories in the magazine conveyed a sense that adventure can be found anywhere for the everyman–even just outside of the city. It is oriented towards this everyman, who is capable of reaching his own potential, if only he tries hard enough (read like traditional Americana or what). The advertisements (at this time) reinforce this theme, with promotions of becoming a better business man, family values, as well as patriotism and nationalism, naturally. This is quite literally laid out at the end of the magazine, where “A Chat With You” leads potential writers into how they should tailor their stories for the magazine. Underpinning these normative performances, we also see simplified and stereotypical representations of People of Colour and immigrants–quite often negative ones at that.